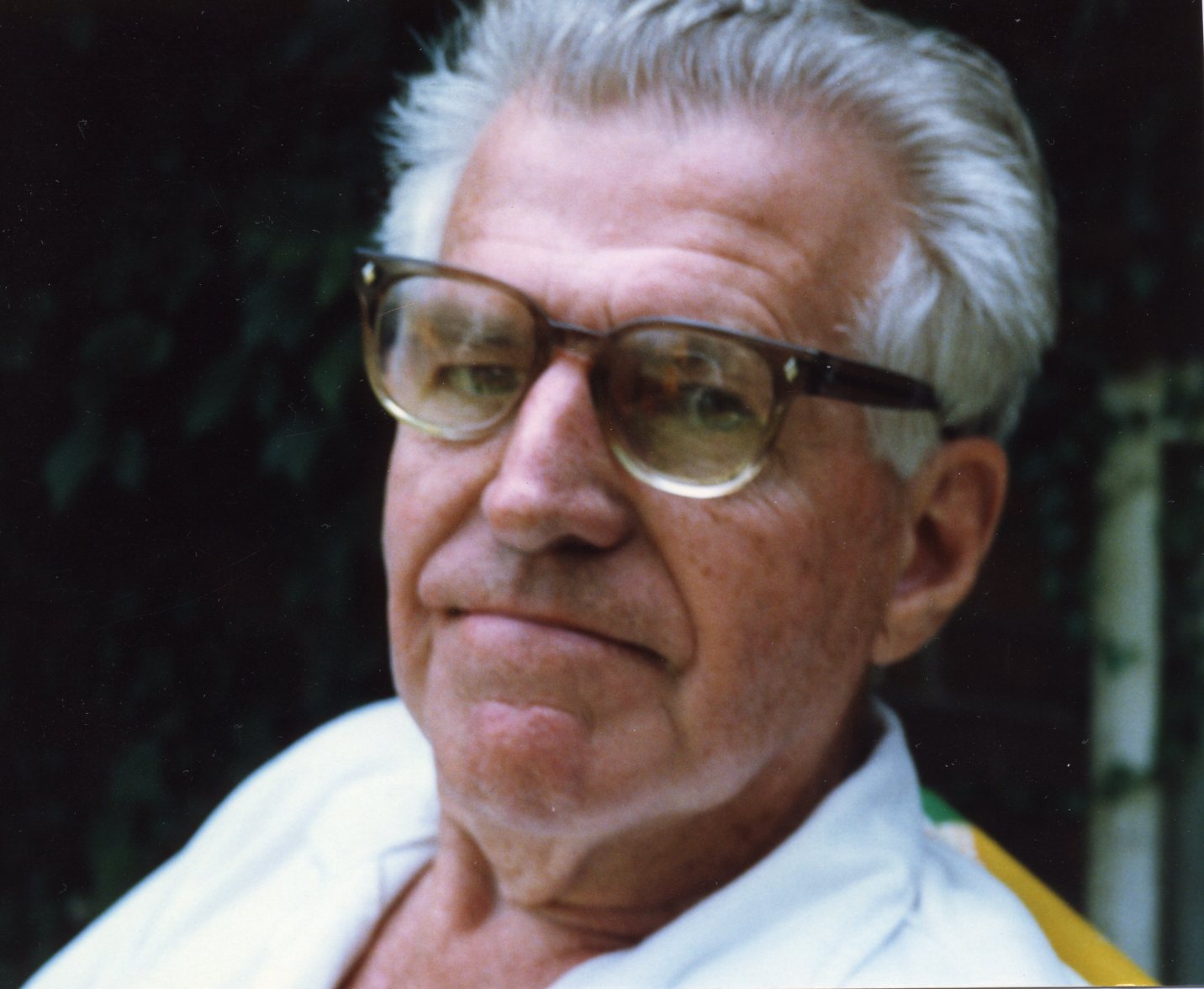

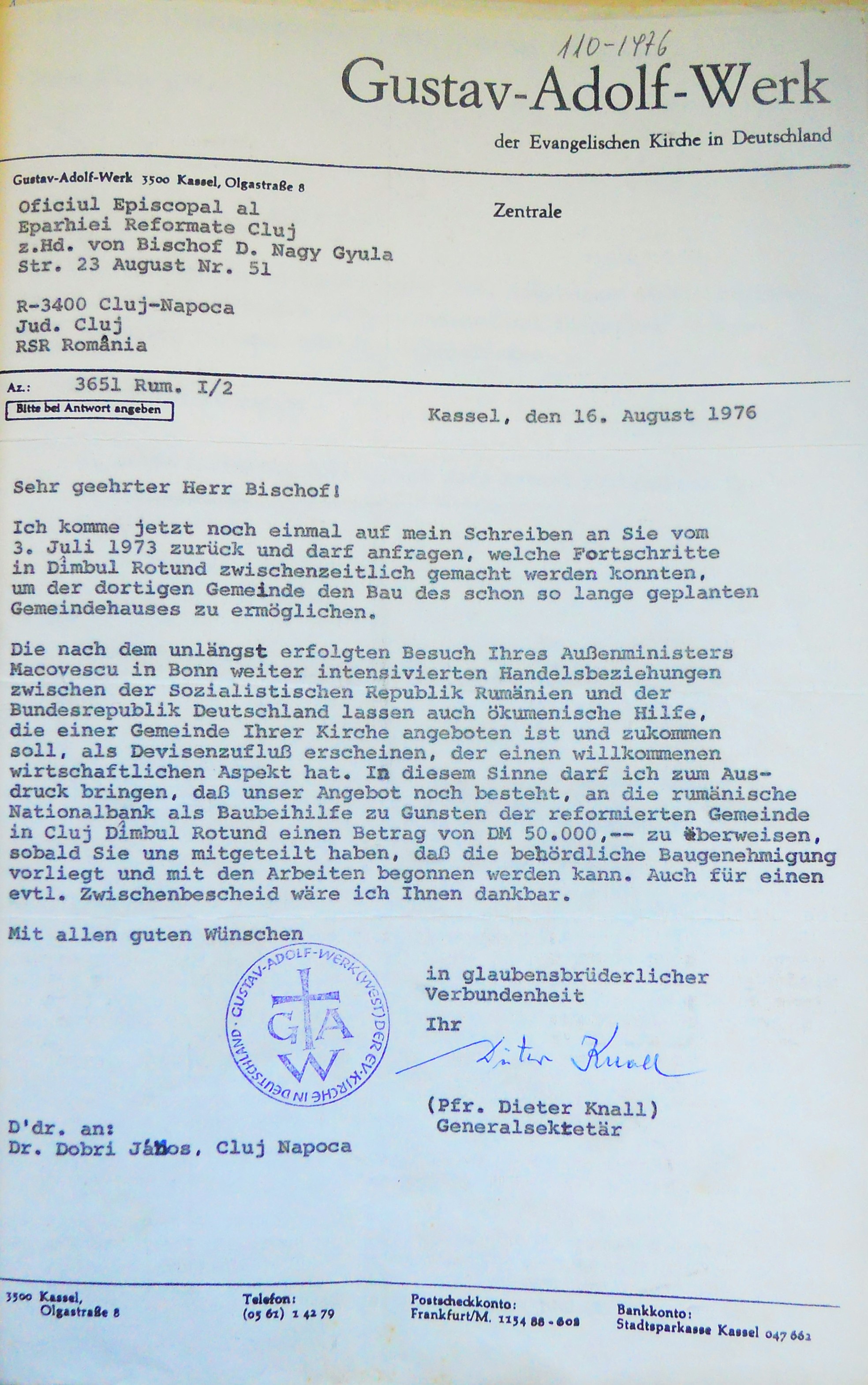

Pe baza documentelor colecției Congregației Reformate din Cluj–Dâmbul Rotund, pe 13 martie 1971, vest-germanul Gustav Adolf Werk a oferit o donație de 50.000 de mărci germane ca ajutor ecumenic pentru construcția bisericii (KKREL 1971/7, Raportul nr. 28). Evenimentul s-a dovedit a fi de importanță majoră în procesul de construcție al bisericii. Faptul că statul putea beneficia de valută străină de pe urma șantierului de construcții a fost considerat un argument foarte puternic și a jucat un rol imens în istoria autorizației de construcție, eliberată însă fără mare tragere de inimă de autorităţile comuniste. Între anii 1971-1976, fundația și pastorul din Dâmbul Rotund, János Dobri, în mare parte doar au corespondat cu privire la această problemă despre preluarea sumei, iar parohia a fost nevoită să răspundă că nu a obținut încă aprobarea pentru construcție. Sub regimul comunist orice donație în bani sau de altă natură pentru comunităţile religioase provenind din străinătate putea fi acceptată și preluată numai cu permisiunea Departamentului Cultelor de la București. Regulamentul nr. 16455/1971 al Departamentului Cultelor, cu referire la Decretul-lege nr. 334/1971 alin. 5 lit. "r", a stipulat că darurile, moștenirile date sau acceptate de organizațiile clericale se pot face numai prin aprobarea Departamentului Cultelor. În plus, orice obiect de inventar, fie că avea valoare istorică, artistică sau nu, cărți, manuscrise, instrumente muzicale, bani, materiale, produse, indiferent de valoarea lor, puteau fi donate sau acceptate numai prin aprobarea prealabilă a Departamentului Cultelor (KKREL 1971/7, Adresa nr.1420). În cele din urmă, în plus față de construcția bisericii, s-a acordat permisiunea pentru utilizarea donațiilor. Conform cunoștinței pastorului reformat András Dobri și a cantorului Anna Jankó, numai prima jumătate a sumei a fost transferată oficial la Banca Națională a României, cealaltă jumătate a fost transferată prin alte „filiere.” În acele vremuri, valuta nu putea intra în posesia unui cetățean român, care trăia în țară, fără aprobarea autorităţilor. Străinii trebuiau să facă schimbul valutar la cursul oficial și astfel puteau să ofere banii. Deoarece rata de schimb era dezavantajoasă, cei responsabili din congregaţie au decis să schimbe valuta introdusă cu ajutorul turiștilor polonezi. Cea mai mare parte obținută în acest fel a putut fi folosită în mod corespunzător în timpul construcției. Pentru că era vorba despre sume mai mari, aproape toți membrii prezbiteriului, format atunci din aproape 28 de membri, au luat o parte din aceste sume, pe care apoi i-au oferit ca donație, în nume propriu, pentru construcția bisericii. Pe baza interviurilor realizate prin metoda istoriei orale, nu este exclus ca a doua parte a donației vest-germane să fie transferată oficial într-un mod similar, iar credincioșii au fost utilizați în preluarea altor donații în numerar străin, pentru că donația în sine a lui Gustav Adolf Werk nu a fost suficientă pentru construcția bisericii (declarația lui Anna Jankó, declarația lui András Dobri).

Materialele create de Securitate despre János Dobri informează, de asemenea, despre donație. Pe baza documentelor conținute în dosarul informativ, la 5 martie 1971, episcopul reformat Gyula Nagy a fost informat printr-o scrisoare din partea donatorului vest-german - prin pastorul-secretar general Dieter Knall - că suma de bani destinată construcției bisericii din Dâmbul Rotund a fost pregătită și i s-a cerut să accepte donația în numele Eparhiei Reformate Cluj. Un răspuns pozitiv a fost precedat de acordul Departamentului Cultelor din București (ACNSAS, 211500/4, 147). Începând din august 1972, serviciul de contraspionaj din Cluj, condus de colonelul Sándor Peres, s-a ocupat, în special, de acest caz. După ce Securitatea a aflat că o sumă considerabilă a fost alocată de Fundația Gustav Adolf Werk pentru construcția bisericii, Peres a afirmat că, pentru a primi banii, ei trebuie să vorbească cu inspectorul județean de la Culte, „studiind posibilele moduri de coordonare.” Această afirmație este semnificativă mai ales în lumina unei declarații ulterioare a inspectorului județean de la Culte, Hoinărescu Țepeș Horia, conform căreia în Cluj nu se vor construi biserici sau capele maghiare, atât timp cât el deținea acea poziție în oraș (ACNSAS, I211500/5, 152–153). Acțiunile ulterioare, construcția bisericii, dovedesc succesul „coordonării,” ținând cont de interesele partidului-stat unic.

Fotografia face parte dintr-o serie mai amplă a colecţiei Oraşul Memorabil, care reflectă şcoala sub comunism. Percepţia uniformelor şcolare în România post-89 reflectă o anumită nostalgie pentru copilăria trăită în anii comunismului (Marin 2013, 10–12), prezentă şi în alte societăţi est-europene. Această nostalgie are ca obiect mai ales anumite jucării, dulciuri, cărţi pentru copii sau, în acest caz, a uniformelor şcolare, care marcau apartenenţa la structuri de înregimentare politică a copiilor, precum şoimii patriei sau pionierii.Cei care au copilărit sub comunism nu îşi reamintesc atât de mult componenta de înregimentare politică, pe care nu o putea înţelege la acea vârstă, cât mai ales anumite detalii care sunt încărcate astăzi cu o valoare sentimentală, precum uniformele, momentele festive, participarea la competiţii. În fotografia de faţă, apar două tipuri de uniforme: uniforma pionierilor la elevul din partea stângă şi cea a şoimilor patriei, la cei doi copii din partea dreaptă. Fotografia a fost realizată în cartierul Steagul Roşu din Braşov, unul dintre cartierele muncitoreşti emblematice ale oraşului, construite la sfârşitul anilor 1940 şi începutul anilor 1950.

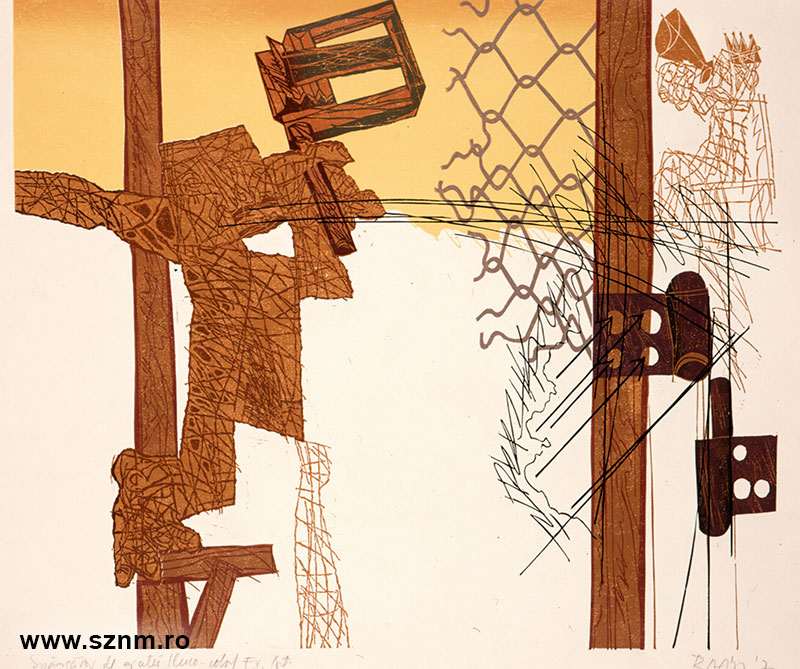

![Imre Baász: Bar breaker [A rácstörő/ Spărgătorul de gratii], linocut, 1976](/courage/file/n129077/5.+R%C3%A1cst%C3%B6r%C5%91.jpg)

Spărgătorul de gratii este una dintre lucrările cele mai iconice ale artistului din această perioadă, combinând virtuozitatea graficii cu atitudinea opozițională într-o singură creație. Imre Baász a fost un grafician în primul rând, care a deconstruit mereu în operele sale formele familiare. Regula deconstrucției este una simplă: nu deconstruim până când nu avem ceva de oferit și de construit în loc. Spărgătorul de gratii a fost făcută imediat după ce artistul s-a mutat la Sfântu Gheorghe de la Cluj-Napoca. Autoritățile județene i-au alocat o casă la Arcuș, un sat în apropierea orașului Sfântu Ghoerghe. În această perioadă artistul s-a familiarizat cu obiectele rurale, care în timp au devenit motive-cheie în opera sa.La Spărgătorul de gratii vedem o figură în picioare distrugând grilajul. Pe partea cealaltă a gratiilor se află o altă figură, așezată pe un scaun încoronat ținând un difuzor. Stilul abstract și percepția geometrică a figurilor este tipică pentru acestă perioadă a artistului.

Atanas Vasilev Patsev was a Bulgarian painter and illustrator. As a secondary-school boy, Patsev joined the communist revolutionary movement and became a partisan.

In 1949, he graduated from the State Academy of Arts, in the class of Prof. Dechko Uzunov.

During the 1960s, his method of work changed in favour of the modern means of the expressive sculpture and painting. In 1968, his exhibition "Weightlessness" provoked confusion among the authorities responsible for the ideological correctness of art. The exhibition was accompanied by a small brochure containing text by the author as well defining weightlessness as a leading principle of the composition. "The form has no weight. It becomes unstable, transparent. The familiar silhouette loses shape. As if the inner construction of the body becomes visible. As if the range of visibility expands. The motion becomes six-way, rotary, supple and undulating" (Patsev, quoted after Iliev 2016: 153). The exhibition took place in a time when the situation in Paris was revolutionary and the Prague Spring was at its height.

Patsev's call for plastic revolution was initially wrapped in silence but afterwards defeating reviews were published: "roughly deformed bodies and practices", "a mixture of styles". The exhibition was attacked for "not containing any new problems" and the author was accused of "discrepancy between theory and practice" (Iliev 2016: 153). The philosophy of weightlessness was perceived as a threat to the regime whose ideology was based on the theorem of control of the Party-state over all processes. "The deprivation of gravity of the person represented is determined as theoretical vandalism similar to anarchism because the concept of the place of the particular individual puts him in a strict rank, together, united, in the group, in the team, at the meeting, at a manifestation. The idea of the different points of view is opposite to the only true uniform line represented by the Party" (Iliev 2016: 153).

Paradoxically, Patsev was simultaneously accused of secession, cubism and expressionism – styles defined by the party ideologists as "noxious", "decadent", "effete" bourgeois forms of plastic thinking.

In the next years, Atanas Patsev created big cycles of paintings on subjects related to the anti-fascist resistance ("Partisan Recollections"). The themes were ideologically orthodox – the events were promoted to mythologized heroism. However, the plastic language did not correspond to the pattern. The paintings of the cycle "The Man and the Things" were perceived as an attack of Patsev on the communist ruling crust tempted by gaining.

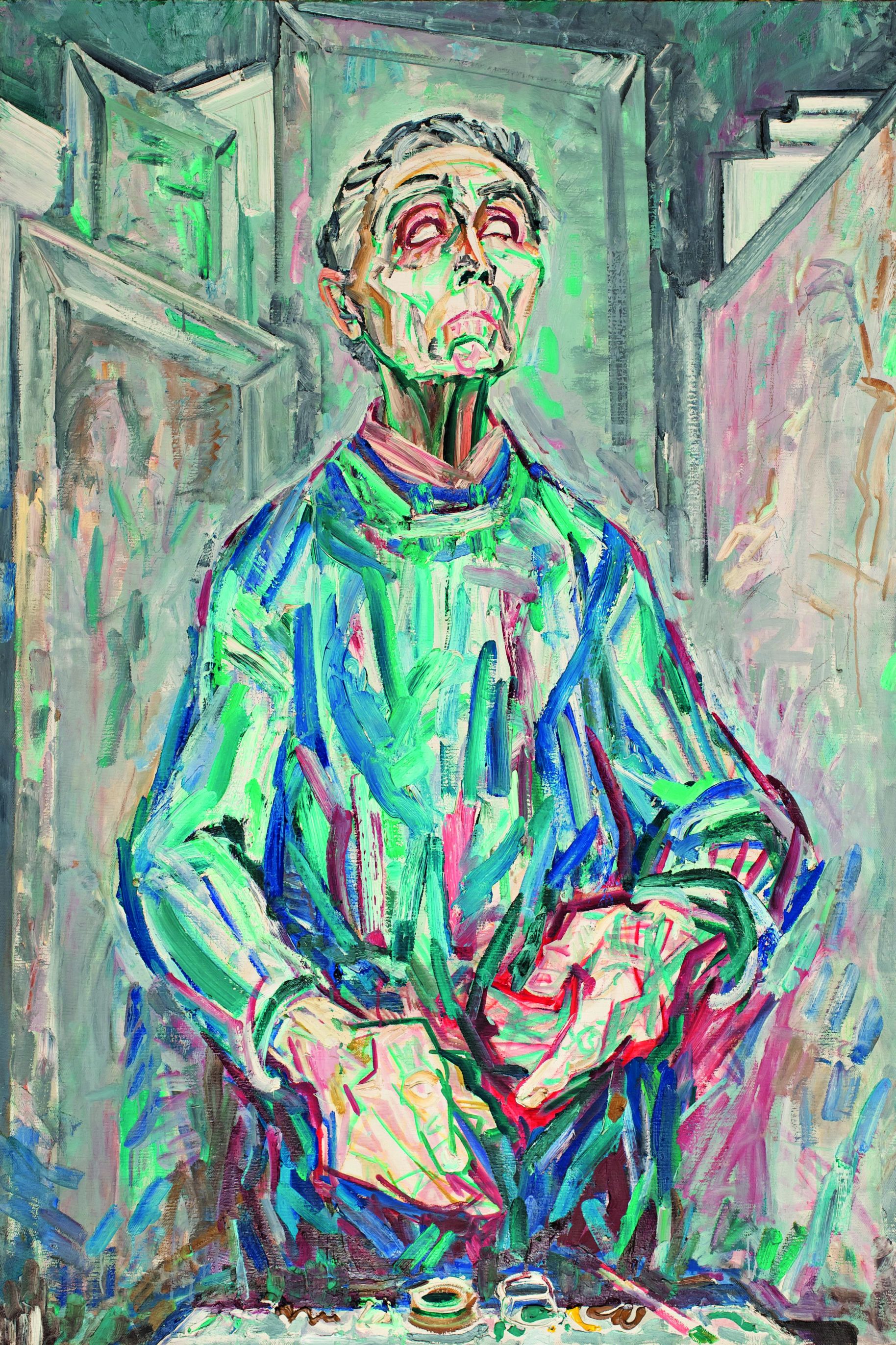

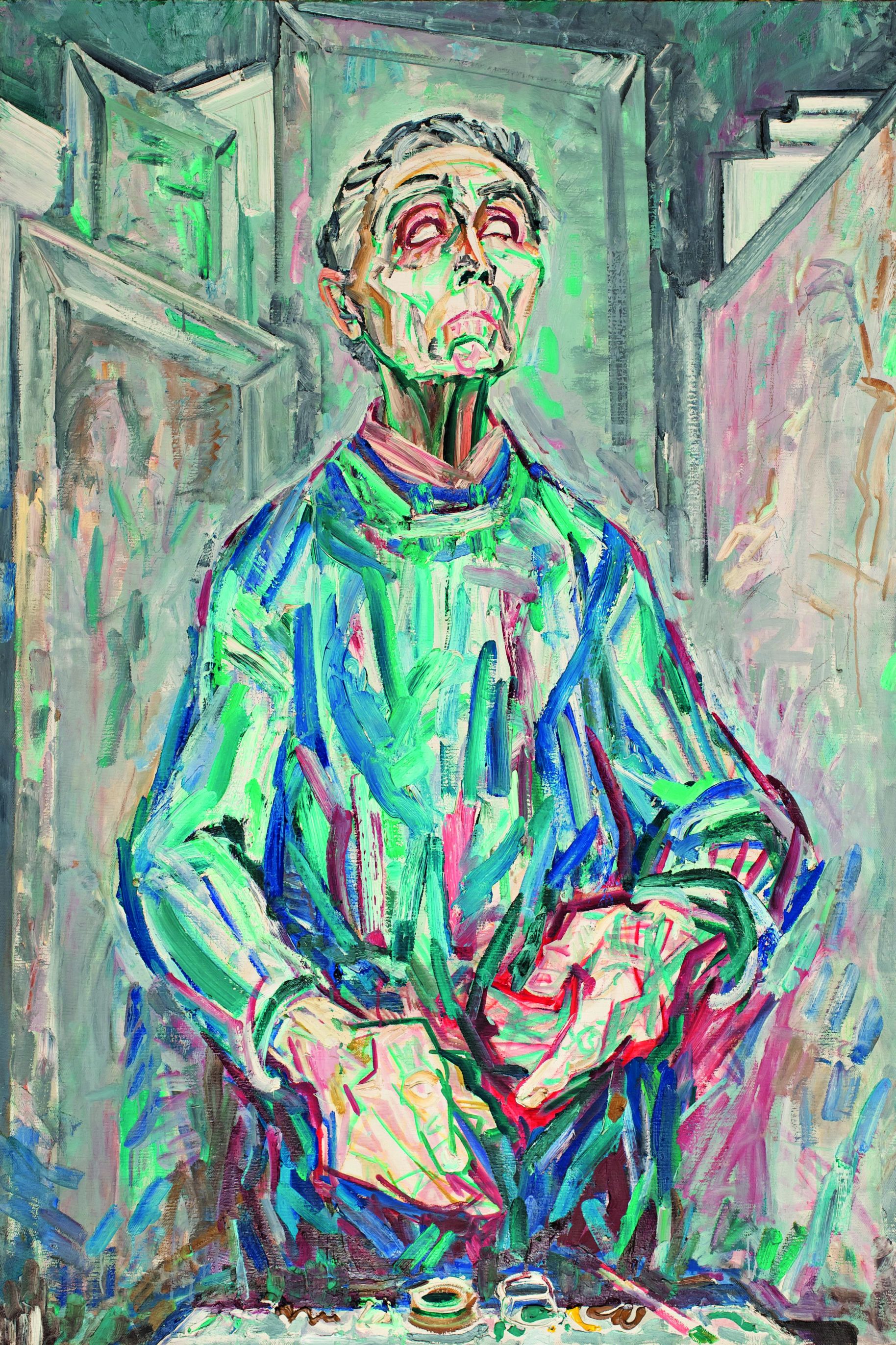

The portraits painted by Atanas Patsev combine "analytical mind and emotional expression" (Iliev 2016: 156). The portrait of Kiril Petrov (1976, Kiril Petrov – a painter who spent many years in estrangement and self-isolation from the public art life after being accused of "formalism") is created with dynamic contrasting colours so that the view of the head is from below and that of the arms is from above. Using the means of perspective, Patsev upsets the balance of the viewer's static contemplation. "Kiril Petrov forecasts through the hatches of Patsev [...] The resistance of Atanas Patsev against the System is the resistance of a man religiously believing in its ideological righteousness, on the one hand, but on the other hand, of a painter who sees its visible ugliness. The painter fights against its main principle – the submission to the rules, standards and instructions. And sometimes, flying on the wings of the subconscious sense of the divine, he manages to escape the locked room of the ideologized mind" (Iliev 2016: 156-157).

There is no monograph published.

Totok, William. Projekt für eine intellektuelle Extermination (Un proiect pentru o exterminare intelectuală), în germană, 1976-1977. Manuscris

Totok, William. Projekt für eine intellektuelle Extermination (Un proiect pentru o exterminare intelectuală), în germană, 1976-1977. Manuscris

William Totok a stat mai mult de opt luni în arest la Securitate în anii 1975-1976 pentru implicarea sa în grupul literar Aktionsgruppe Banat, considerat subversiv de regimul comunist, precum şi pentru critica sa faţă de regimul Ceaușescu. Totok a fost eliberat în 1976, după publicarea în ziarele Frankfurter Rundschau şi Le Monde a unor articole care prezentau abuzurile autorităţilor comuniste în cazul său. După eliberarea sa, Totok a redactat o primă versiune a memoriilor sale din perioada arestării şi detenţiei intitulată “Projekt für eine intellektuelle Extermination” (Un proiect pentru o exterminare intelectuală), în care a relatat experienţele sale ca deţinut politic. În mai 1982, Securitatea a întreprins o percheziţie la domiciliul său şi la unul dintre prieteni, scriitorul german din România Horst Samson. Cu această ocazie, mai multe documente au fost confiscate, inclusiv un exemplar al manuscrisului memoriilor mai sus menţionate (ACNSAS, I 210 845, vol. 2, 265–66; Totok 2001, 107–108). În acest manuscris, Totok a relatat în detaliu condiţiile din penitenciarul din Timişoara, unde a fost închis, interogatoriile la care a fost supus, dar şi povestea unei scrisori redactată de acesta între cele două perioade de detenţie (Totok a fost eliberat pentru o perioadă scurtă în octombrie 1975 deoarece a fost arestat din nou în noiembrie 1975). În această scrisoare, trimisă de mama sa în Republica Federală Germania (RFG) după a doua arestare a acestuia, Totok relata evenimentele dramatice ale arestării lor abuzive din octombrie 1975, precum şi hărţuielile la care au fost supuşi de poliţia secretă. Din fericire, exemplarul confiscat de Securitate nu a fost unicul, iar Totok a reuşit să ascundă o copie şi să o trimită în RFG după emigrarea sa în martie 1987. În 1988, Totok a publicat o ediţie revizuită şi extinsă a acestuia sub titlul: Die Zwänge der Erinnerung: Aufzeichnungen aus Rumänien (Constrângerea memoriei: amintiri din România).

A special music collection was created by two librarians in a public library in Budapest. This unique repository was established in the branch library of the Metropolitan Ervin Szabó Library (Fővárosi Szabó Ervin Könyvtár, FSZEK). The librarians maneuvered among the barriers of the regime and utilized a loophole which allowed them to copy music recordings. The collection consists of recordings of contemporary Western music and alternative Hungarian bands. The materials reflect the tastes of the librarians.

The five-page first version of the Charter 77 Declaration was established in the second half of December 1976 (date 26 December 1976), its basic content was agreed on the 11th December of the same year. Red notes were from Václav Havel, pencil notes from Paul Kohout. The declaration is a founding document of the Charter 77, which criticised state power for the non-observance of human and civil rights in Czechoslovakia. Originals of three drafts of this Declaration was handed over by Pavel Kohout to the contemporary Swiss Ambassador and after Kohout´s forced exile the texts were returned to him. About next 25 years these versions were deposited in Vienna and in Prague and since 2012 have become a part of the Moravian Museum´s collections. Because of the material’s high value, a copy of the Declaration is very often exhibited, illustrating the mapping of the Communist regime.

Vytenis Andriukaitis made the university’s flag according to a description by Viktoras Kutorga. All the parts of the flag, like the colour and the emblems, had a meaning, and the composition had a philosophical basis. The colour yellow symbolised a microcosm, and black symbolised a macrocosm. The colour green meant harmony and ecology, and red symbolised the people’s humanistic altruism. The flag has survived until today. Vytenis Andriukaitis keeps it in his office in the EU Commission in Brussels.

Czech poet, writer and Nobel Prize holder Jaroslav Seifert sold the manuscript of his memoirs “Všecky krásy světa” (All Beauties of the World), altogether 784 pages written between 1970 and 1975, to the Museum of Czech Literature in 1978. The sale, which was in negotiation since 1976, was realised based on an agreement with Marie Krulichová, the Literary Archive of the Museum of Czech Literature acquisition staffer, and with the help of an antiquarian book shop on Wenceslas Square 41 in Prague. The manuscript “Všecky krásy světa” became the foundation of the Jaroslav Seifert Collection in the Literary Archive of the Museum of Czech Literature, which expanded in the following years and now includes 63 boxes.

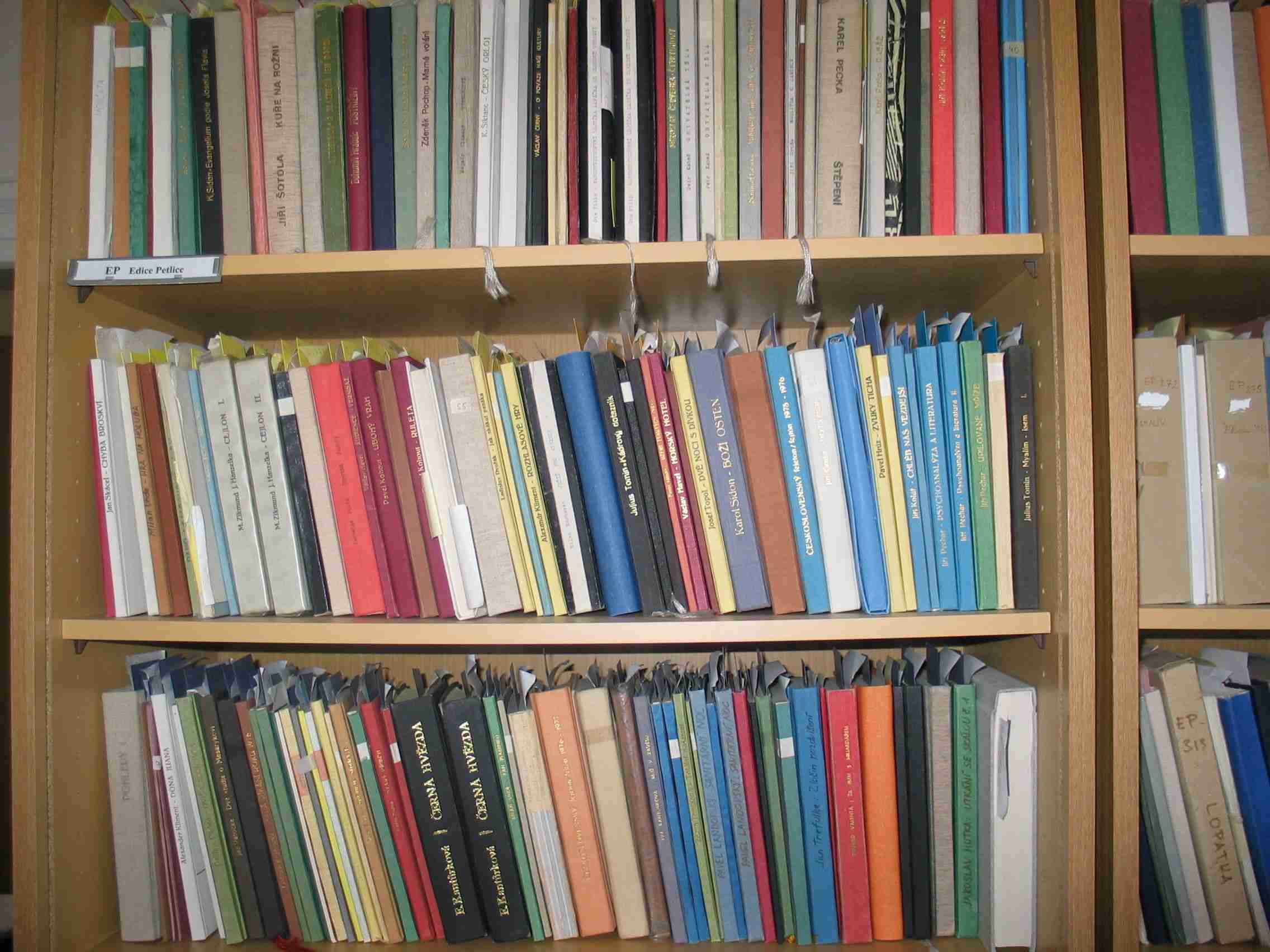

This unique collection of samizdat literature (1972-1989) contains samizdat books by Czech and Slovak authors whose works could not officially be published in socialist Czechoslovakia, as well as a collection of samizdat periodicals and individual texts.

Franjo Nevistić i Vinko Nikolić, Bleiburška tragedija hrvatskoga naroda [The Bleiburg tragedy of the Croatian people], 1976. Knjiga

Franjo Nevistić i Vinko Nikolić, Bleiburška tragedija hrvatskoga naroda [The Bleiburg tragedy of the Croatian people], 1976. Knjiga

The subject of Bleiburg was banned in Yugoslavia, both in public discourse and in the scientific community (scientific research was forbidden). The topic was treated freely only in the diaspora, and the book The Bleiburg Tragedy of the Croatian People presents the most systematic treatment of the subject. An additional fact is that it was originally published in the Spanish language (1963).

Václav Havel (1936-2011) was an important Czech playwright and essayist, a critic of the communist regime, one of the initiators of Charter 77, a founding member of VONS (The Committee for the Defence of the Unjustly Prosecuted), a political prisoner and later president of Czechoslovakia and the Czech Republic. The collection consists mainly of materials of his dramatic creation and its dissenting effect.

The photography made by Tomasz Sikorski documented Edward Dwurnik’s painting action Wykonanie portretów psychologicznych studentów D.S. „Babilon” (Making of psychological portraits of the students from ‘Babylon’ Dormitory) at the Mospan Gallery. The action took place on May 31, 1976. Between 6 PM and 9 PM, Edward Dwurnik painted 28 images of the students living in the dormitory which the Mospan Gallery was associated with. The portraits were made by acrylic paints on the one huge canvas. The canvas was at the end cut into 28 pieces so every participant of the action could take his or her psychological image with his or her name and surname. Dwurnik’s performance was an exceptional event at the Mospan Gallery, one of a few that were addressed directly to the students from the ‘Babylon’ Dormitory of the Warsaw University of Technology.

În condiţiile unor constrângeri severe pe care politicul le exercita asupra activităţii arhitecţilor în perioada comunistă, pictura de acuarelă a devenit pentru Gheorghe Leahu o formă de evadare. Arhitectul Leahu a fost atras de “acuarela de arhitectură” deoarece această activitate îi permitea să îşi aleagă singur temele şi maniera de abordare, o libertate de creaţie de care nu se putea bucura în activitatea profesională. Fiind un mare iubitor al patrimoniului arhitectural al Bucureştiului, acesta a ales să picteze cu precădere peisaje pitoreşti din centrul vechi al capitalei, dar şi din alte oraşe din ţară. Conform propriei mărturisiri, “acuarela de arhitectură” a reprezentat şi o formă de a lăsa “un document” despre un patrimoniu aflat în acei ani în pericol. Din cauza ambiţiilor megalomane ale lui Ceauşescu de a remodela capitala conform concepţiei sale despre cum trebuia să arate un oraş socialist, zone întregi din centrul vechi au fost demolate în decursul anilor 1980.O serie de acuarele ale lui Leahu reprezintă Mănăstirea Văcăreşti, unul dintre cele mai importante monumente istorice ale Bucureştiului, distrusă în 1986. Una dintre aceste acuarele, pictată în 1976, se intitulează “Mănăstirea Văcăreşti înainte de furtună.” Pictura reprezintă o panoramă cu complexul mănăstirii, construit la începutul secolului al XVIII-lea. Titlul dat atunci de către autor acuarelei conţine o aluzie neintenţionată privind destinul tragic al monumentului. În calitate de şef de secţie în cadrul Institutului Proiect Bucureşti, instituția de stat care se ocupa de proiectele de arhitectură şi urbanism în capitala României, Leahu a fost însărcinat să coordoneze în 1984 o echipă de arhitecţi în vederea proiectării noului tribunal al capitalei. Conform indicațiilor lui Ceauşescu, acest nou edificiu urma să fie ridicat pe amplasamentul Mănăstiri Văcăreşti. Echipa coordonată de Leahu a furnizat autorităţilor doisprezece planuri diferite ale viitoarei construcţii prin care se putea salva cea mai mare parte a complexului mănăstirii. Toate aceste eforturi au fost însă fără succes deoarece în 1986 autorităţile au decis demolarea sa completă. Astfel, acuarela a devenit un “document” privind una dintre cele mai valoroase monumente distruse de politicile urbane ale regimului Ceauşescu. Aceasta a fost reprodusă în unele albume şi cărţi ale arhitectului. Una dintre aceste cărţi a fost dedicată chiar demolării monumentului: Distrugerea Mănăstirii Văcăreşti (1997).

Professor Kathy Hillman highlighted autographed volumes by Alexander Solzhenitsyn as rare items in the Keston Collection. They require special handling and are not digitized. The publication is the 1974 London Book Club Associates edition translated from the Russian by Thomas P. Whitney. Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn personally inscribed the book to Jane Ellis on February 26, 1976. Ms. Ellis worked for the Keston Institute for nearly 20 years, serving on the editorial board of Keston’s journal Religion in Communist Lands (later titled Religion, State & Society), including 5 years as editor. She also founded Aid to Russian Christians (ARC).According to her obituary published by Philip Walters in Religion, State & Society in 1998, the ARC was the first organisation with the aim of systematically supplying material aid and spiritual support to Orthodox Christians in Russia. She remained the organization’s director until 1986. For the first four years of its existence, Jane Ellis ran the organization alone, operating out of a tiny bedsit in London. She wrote hundreds of letters asking for support for faith communities in the Soviet Union. She joined the Keston Center immediately after graduating from the university in 1973, where she translated documents, gave lectures, wrote articles for scholarly journals and edited volumes, and broadcast for the BBC in both Russian and English. She travelled widely within the USSR and wrote two monographs about the Russian Orthodox Church, which were received with acclaim in Russia. She also promoted interfaith discussions and cooperative projects.

The collection holds documentation on the activities of the Strazdelis University, which operated underground in Lithuania in the 1970s. The aim of the Strazdelis University was to provide alternative education on a voluntary basis, organising and inspiring self-education in the humanities and social sciences. Much attention was paid to ethnography and the study of Karl Marx, interpreting his works differently to how Soviet ideology did. The Strazdelis University was the first step in anti-Soviet or non-Soviet actions for a group of people who later, during the period of Sąjūdis (the Lithuanian national movement, 1988-1990), became activists and founders of modern political parties. The collection is stored in the private papers of Vytenis Povilas Andriukaitis, the EU commissioner, who was a member and dean of the university.

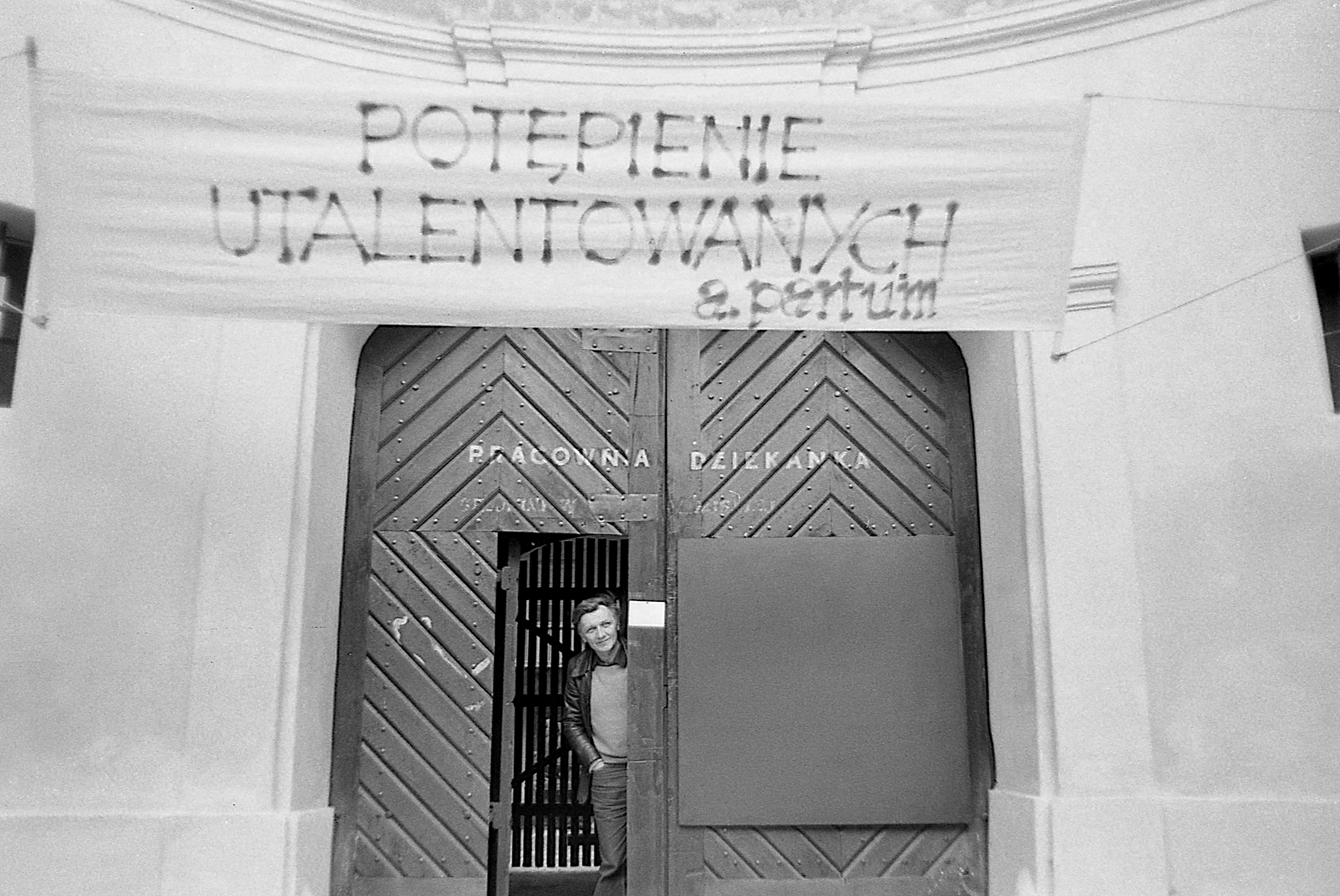

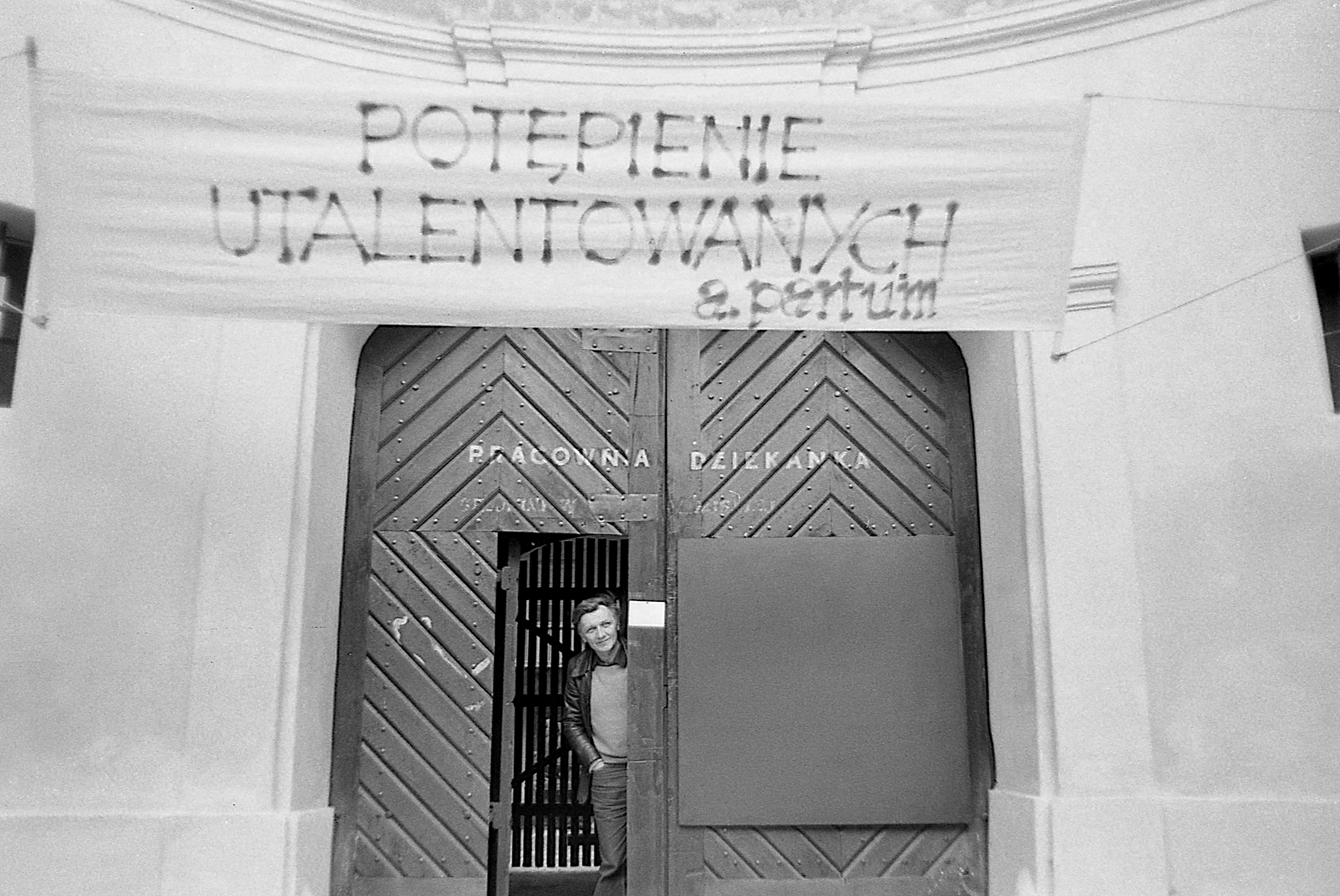

The collection is about the activities of the Dziekanka Students' Art Center and Dziekanka Workshop (Pracownia Dziekanka) in the years 1976-1987. Under these two names was the same place, an extraordinary interdisciplinary artistic and educational laboratory, combining the debuting students of Warsaw's art academies and outstanding artists from Poland and abroad. Around the studio, a unique milieu was created, combining post-Fluxus artists interested in new media and avant-garde theatre ventures, but also painters and sculptors of new expression or punk music bands. The years 1976-1987 is the most intense, though the heterogeneous period in the history of Dziekanka, filled with exhibitions, performances, shows, discussions and social life. During this time Tomasz Sikorski was an active participant in events at Dziekanka, and from 1979 he was the co-director of the institution. Owing to his constant presence and managerial function, Sikorski gathered an extensive collection of photos and other materials documenting the functioning of the initiative, going beyond the definitions of independent galleries.