Croatian scholars made important contributions to the work of the Pugwash Movement by gathering primarily around the Institute for the Philosophy of Science and Peace of the Yugoslav (after 1991 Croatian) Academy of Sciences and Arts (JAZU/HAZU). In 1966, a group of Croatian intellectuals from the Institute, led by Ivan Supek, in 1966 launched the journal Encyclopaedia moderna: časopis za sintezu znanosti, umjetnosti i društvene prakse. It was published in all Yugoslav languages and dialects, but there were also articles in English. In addition to the central editorial office in Zagreb, it had editorial staffs in Belgrade, Ljubljana, Sarajevo, Skopje and Titograd. It was issued quarterly, although occasionally deviated from this schedule. The editor in chief was Ivan Supek (except in 1975, when the editor was Eugen Pusić). Since the mid-1980s, Supek was assisted by Nikola Zovko and Bojan Marotti (interview with Marotti, Bojan).

As a multidisciplinary journal, it promoted universalism and a humanistic orientation for science and the arts, as well as the complete disarmament and the creation of world peace. The first issue began with the “A Word from the Editors,” in which they stress: “we stand between military, economic and ideological blocs, and it is clear that in the event of a [global] conflict there can be no victory, but only a general disaster” (p. 1). They insisted on the universality of humankind: “Although the world is so fatally disunited, in every corner of it peaceful, humane and progressive thought is smouldering" (p. 3).

The goals of the journal were almost identical to the goals of the Pugwash Movement, and Supek insisted that every issue must contain something about the movement. “Pugwash” or “Peace Studies” or some column with a similar name was published in almost every issue. It would usually convey information, documents, declarations, or reports from Pugwash Conferences and other meetings. All of the contributions in the column were in English, in attempt to make the journal accessible to international scientific currents.

In the 1960s, Encyclopaedia moderna was relatively popular due to the prominent intellectuals who contributed articles to it. The journal strived for academic freedom and was even open to topics that the communist government considered undesirable, as was the case with religion (Kolarić 1973). The Yugoslav communist authorities did not like such intellectual independence, and the government reduced the funding for all of Yugoslavia's Pugwash organisations and publications. In 1976, Encyclopaedia moderna was forced to shut down because the government completely severed its funding (Knapp 2013, 99). In the 1980s, the very existence of the Pugwash organisation in Yugoslavia was questionable, mainly because Supek was out of favour with the communist regime. Still, the movement survived those trying years.

The journal was re-launched after the fall of communism in 1991, with Nikola Zovko as editor-in-chief, but its scope was oriented more towards Central Europe. It was published until 1998, and Marotti believes the journal was "naturally extinguished" because the themes of the journal were no longer as current as during the Cold War (interview with Marotti, Bojan).

This document is one of the reasons for the political fall of Većeslav Holjevac, the president of the Emigrant Foundation of Croatia (EFC), because it led to charges of his nationalist activity. The members of the Commission for the Examination of Nationalist Phenomena in the EFC faulted the Charter’s text for its frequent emphasis on national adjective ("Croatian people," "Croatian language," "Croatian emigrants," "Croatian nationality") over the more accepted terminology ("emigrants," “our emigrants,“ “emigrants from Croatia," etc.).

Namely, the communist government did not support this emphasis on national qualities; rather it resolved the national question in heterogeneous Yugoslavia by imposing the "supranational" ideology of "fraternity and unity," which was supposed to act as an integrative factor. Consequently, cultural institutions were not allowed to carry the name "Croatian" but rather ”of Croatia.“

By 1995, the document was, along with the other records of socio-political organisations, a part of the Archives of the Institute of History of the Labour Movement of Croatia/Institute for Contemporary History. That year, in July, it was handed over to the Croatian State Archives (CSA) where it is kept today. The documents are accessible for use without any restrictions.

Izvještaj o Uskrsnoj poslanici Svetoga arhijerejskog sinoda Srpskoh Pravoslavnoj Crkvi, na hrvatskom, 1966. godine

Izvještaj o Uskrsnoj poslanici Svetoga arhijerejskog sinoda Srpskoh Pravoslavnoj Crkvi, na hrvatskom, 1966. godine

The letter of the Commission on Religious Matters of the Vinkovci Municipal Assembly to the correspondent commission at the republic level on the activities of Serbian Orthodox Church at the time of Easter in 1966 contains the entire epistle that was read in all Orthodox churches in the Vinkovci Municipality. This was an example of how the regime also attempted to exert control over the Serbian Orthodox Church by collecting the information on almost all of its religious activities. As a religious institution, the Serbian Orthodox Church was also regarded as a source of anti-socialist policy. “In addition to increased activity by the Roman Catholic Church, we may also notice in the Orthodox Church a growing activity, which can be seen in the number of believers, organisational arrangement, the formation of ecclesiastical associations and the new religious buildings,“ it says in the letter.

În urma arestării lui Mihai Moroșanu, la sfârșitul lunii iulie 1966, și a procesului său desfășurat ulterior, sentința în acest caz a fost emisă la 2 noiembrie 1966. Ca și în alte cazuri similare, textul sentinței rezuma și descria cu atenție delictele lui Moroșanu și „crimele” pe care le-ar fi comis împotriva sistemului sovietic. Potrivit acestui document, începutul activității sale de opoziție deschisă față de regimul sovietic putea fi identificat cel puțin din anii săi de studenție în cadrul Institutului Politehnic. Chiar înainte de exmatricularea sa din institut, în octombrie 1964, din cauza implicării sale în depunerea unei coroane de flori la monumentul lui Ștefan cel Mare, el ar fi manifestat un comportament „ne-sovietic”. Astfel, potrivit mărturiilor câtorva dintre colegii săi, Moroșanu „a distorsionat sistematic și în mod intenționat realitatea sovietică; în mod deschis, în prezența altor studenți, și-a exprimat nemulțumirea față de ordinea social-politică existentă în țara noastră și a făcut adesea declarații nocive și tendențioase cu privire la diferite aspecte ale dezvoltării economice și culturale a RSSM.” Chiar dacă aceste acuzații generale erau, în sine, destul de grave din punctul de vedere al autorităților sovietice, ele păreau aproape banale în comparație cu opiniile sale naționaliste. Moroșanu a fost acuzat de „erijarea într-un presupus apărător” al culturii și artei naționale moldovenești și, cel mai important, de „propagandă intenționată a ideilor sale, pline de conținut naționalist și șovinist, care promovau dușmănia și relații ostile între diferite naționalități sovietice”. Documentul este destul de revelator în legătură cu rădăcinile personale ale opoziției lui Moroșanu față de regim. Atitudinea sa anti-sovietică a fost provocată inițial de deportarea familiei sale și, mai ales, de arestarea și condamnarea tatălui său la șapte ani de muncă forțată, în 1949. Istoria și originea socială a familiei lui Moroșanu era un factor care provoca și mai multă neîncredere din partea regimului, nu numai din cauza identificării lor drept „chiaburi”, ci, de asemenea, și pentru că tatăl său ar fi fost, chipurile, „conducătorul unei secte a Martorilor lui Iehova, ceea ce a avut un impact evident asupra educației lui Moroșanu”. Din câte se pare, activitățile sale s-au intensificat începând cu vara anului 1963, când, în timpul unei discuții despre poetul Evgeni Evtușenko, Moroșanu încerca să-i convingă pe colegii săi că presa sovietică „mințea”. Cu această ocazie, el și-a manifestat, de asemenea, „ura” față de comuniști. Mai mult decât atât, Moroșanu „propaga printre studenți anumite idei cu un caracter naționalist și șovinist, cerându-le colegilor săi să îi vorbească doar în moldovenește”. De asemenea, el a condamnat în mod deschis aflarea statuii lui Lenin în piața principală a orașului, argumentând că aceasta ar fi trebuit înlocuită de monumentul lui Ștefan cel Mare. Astfel, incidentul legat de ceremonia de la statuia lui Ștefan cel Mare a fost interpretat ca reprezentând punctul culminant al numeroaselor acțiuni inspirate de naționalism întreprinse de către Moroșanu. Sentința justifica decizia de exmatriculare a lui Moroșanu de la universitate. În același timp, acest document sublinia, de asemenea, că, în timpul activității sale ca muncitor la fabrica de beton armat din Chișinău, Moroșanu și-a continuat activitățile sale de propagandă ostilă regimului. Referindu-se la mai multe depoziții ale martorilor, instanța a conchis, că aceste acțiuni urmăreau „răspândirea urii rasiale și naționale în rândul muncitorilor acestei fabrici”. În mod concret, Moroșanu a fost acuzat că și-a exprimat în mod deschis opiniile, conform cărora „în RSS Moldovenească ar trebui să se vorbească numai moldovenește, toate denumirile și inscripțiile oficiale ar trebui să fie scrise numai în limba moldovenească, că limba moldovenească ar trebui să folosească doar grafia latină, deoarece ea aparține grupului de limbi romanice, astfel încât alfabetul rusesc este străin pentru limba moldovenească, iar persoanele de naționalitate „ne-moldovenească” nu au nici un drept de a lucra în Moldova dacă nu vorbesc moldovenește”. Pentru a completa această imagine destul de gravă pentru regim, Moroșanu ar fi manifestat tendințe anti-ruse și comportamente ocazional antisemite față de colegii săi. El condamna, de asemenea, revizuirea frontierelor basarabene în 1940, când regiunile nordice și sudice ale acestei provincii au fost transferate sub controlul RSS Ucrainene, în timp ce restul Basarabiei a fost unită cu RASSM pentru a forma noua RSSM. Moroșanu argumenta că aceste teritorii erau „ocupate de către ruși” și fuseseră „transferate ilegal către RSS Ucraineană”. În acest context, nu este surprinzător faptul, că incidentul survenit în magazinul din Chișinău, din 28 iulie 1966, care a condus la arestarea acestuia, a fost interpretat ca o manifestare periculoasă a „naționalismului și șovinismului”, precum și ca „o încălcare gravă a ordinii publice”. Această concluzie era în perfectă concordanță cu atitudinea din ce în ce mai intolerantă a autorităților față de orice manifestare a „naționalismului local”, evidentă la sfârșitul anilor 1960. Situația lui Moroșanu a fost, fără îndoială, agravată de refuzul său de a-și recunoaște vinovăția, precum și de persistența sa în manifestarea „caracterului greșit și pernicios al opiniilor sale, care erau orientate către propagarea dezbinării naționale și provocarea urii față de persoanele de altă naționalitate”. Mai mult decât atât, el chiar „a încercat să exprime și să propage aceste păreri pe parcursul întregii anchete judiciare.” Moroșanu a recunoscut numai parțial că a comis o ”greșeală” în timpul colectării semnăturilor din partea studenților pentru a protesta împotriva mutării monumentului lui Ștefan cel Mare. Refuzul său încăpățânat de a se supune voinței acuzatorilor săi, precum și eșecul său de a se „pocăi” și de a-și face autocritica au fost luate în considerare în cadrul sentinței finale a instanței, care sublinia „gravitatea și pericolul social deosebit” al „crimei” pe care ar fi comis-o Moroșanu. În pofida handicapului său fizic, pe 2 noiembrie 1966, inculpatul a fost condamnat la trei ani de închisoare, în baza articolului 71 (subminarea egalității naționale și rasiale a cetățenilor sovietici) și a articolului 218, partea 1 (huliganism cu circumstanțe agravante) din Codul Penal al RSS Moldovenești. Probele materiale legate de cazul lui Moroșanu au fost considerate „fără nici o valoare”, fiind ulterior distruse. Sentința lui Moroșanu este revelatoare pentru „ierarhia comportamentelor periculoase” construită de către autoritățile sovietice în această perioadă. Naționalismul local era, în mod evident, una dintre cele mai condamnabile forme de opoziție față de regimul comunist, mai ales la periferia statului sovietic.

Having been sent to the provinces of Lithuania in 1966, the ex-Soviet political prisoner and Catholic priest Fr Stanislovas made Paberžė an attractive place for the intelligentsia and people who shared non-Soviet attitudes. Fr Stanislovas became widely known in Lithuania for his deep sermons and his ability to attract and engage people through various initiatives, like collecting, repairing and restoring old things, his philosophical attitude towards things (similar to that of Rainer Maria Rilke), and the importance of activity. The items (material objects) in the collection are a testimony to the environment in which the cultural opposition led by Fr Stanislovas discussed political, religious and social issues during Soviet times.

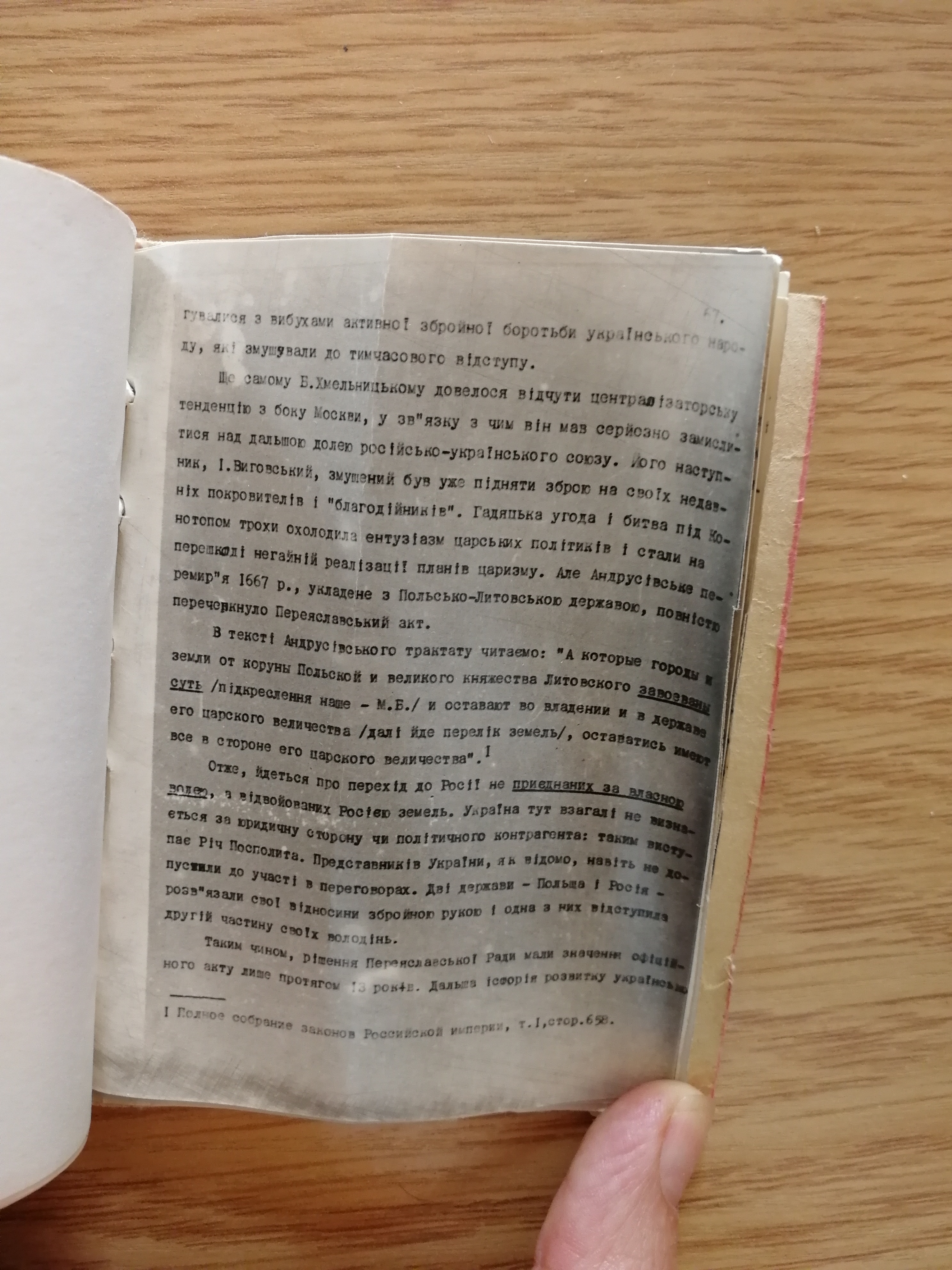

This samizdat miniature with its photocopied (from a microfilm) and manually bound pages represents a typical form of smuggling underground materials from Soviet Ukraine. Microfilms and miniature forms were the only way to safely smuggle abroad illegal literature and documents from the Soviet Union.

This samizdat book was rolled and hidden in a luggage of a Smoloskyp courier. This was the way how Smoloskyp couriers managed to smuggle many other Ukrainian samizdat and dissident materials, including Bil’mo by M. Osadchyi, O. Berdnyk’s manuscripts, the entire collection of the documents of the Ukrainian Helsinki Group, D. Shumuk’s memoirs, a photo collection belonged to M. Rudenko, and so on. The obtained materials were later published in both Ukrainian and English, and were circulated in international media.

Mykhailo Braichevsky wrote his article Priednannia chy voz’ednannia? (Annexation or Reunification?) in 1966 in which he openly criticised the Theses on the 300th Anniversary of the Reunification of Ukraine and Russia (1654-1954), a document imposed by the Communist Party of the Soviet Union in 1954 as the only permitted interpretation of the events of 1654 in Ukrainian history, namely, the Pereiaslav Council and the Treaty of Pereiaslav, after which Ukraine became a part of the Russian Empire. Braichevsky’s work was circulated in samizdat in Ukraine, smuggled abroad, and was published in Canada as a brochure. As a result of this writing, Braichevsky was fired from the Institute of History, where he worked as a researcher. In the next decade he was oppressed by the Soviet authorities and the Communist Party that demanded his public “repentance” and acknowledgment of his research “falsities.” He was not allowed to officially continue his research career.

![Maróthy, János. Zene és polgár, zene és proletár [Music and Bourgeois, Music and Proletar], 1966. Book](/courage/file/n35318/marothy-janos-zene-es-polgar-zene-es-proletar-842907-nagy.jpg)

Maróthy, János. Zene és polgár, zene és proletár [Music and Bourgeois, Music and Proletar], 1966. Book

Maróthy, János. Zene és polgár, zene és proletár [Music and Bourgeois, Music and Proletar], 1966. Book

There were changes in the history of Hungarian scholarship on music in the 1960s. Researchers started to analyze the personal and collective dimension of the reception and to think about how the historical past could be interpreted through popular music.

The two symbolic dates were 1962 and 1966. In 1962, József Ujfalussy’s book A valóság zenei képe [The Musical Image of Reality] was published, in which he examines the texture of the music and the places and ways in which it was presented. In 1966, János Maróthy’s major work, Zene és polgár, zene és proletár [Music and Bourgeois, Music and Proletarian], was published. In his book, he elaborated on the different types of music in the twentieth century. He studied the relationships between the bourgeois worldview and bourgeois music, as well as connections between the folk song and bourgeois music forms and historical types of the folk song. In his book, Maróthy dedicated a section to the relationships between folk and mass music, emphasizing the music of the workers and trying to examine the effects of folk music on workers’ culture. Maróthy turned away from the main directions of the local discussions on jazz. He was interested in the social roots of this type of music, its relationships to folk music, and its labor movement backgrounds. This book is one of Maróthy’s publications which had effects on later research methods.

Această colecție se axează pe cazul lui Gheorghe Muruziuc, o persoană originară din rândul clasei muncitoare, care și-a exprimat opoziția față de regimul sovietic prin arborarea drapelului românesc pe acoperișul fabricii unde lucra, în iunie 1966. Acesta a fost primul caz de arborare publică a tricolorului românesc pe teritoriul Republicii Sovietice Socialiste Moldovenești (RSSM), după iunie 1940.

Ernst Museum, Budapest, 16 April - 8 May 1966 One of the determining agents in the organization and history of the Studio of Young Artists was the board and the views represented by its members. After the election in 1964, artistic freedom and the integration of different tendencies became a priority. The board established a theoretic panel (for cultural-political reasons, the collaboration of artists and art historians earlier had not been nurtured or supported), and it encouraged members to be freer in their expressive experiments.

Negotiating with the ministry (and personally with the main cultural political decision-maker, György Aczél) the chairperson, István Bencsik, received permission to hold a “jury-free” exhibition (which meant that only board members would select the works due to spatial limitations). This “yearly exhibition” was the first to display non-figurative works, which were on exhibition in a separate room (with a surrealist and a pop-section as well).

The exhibition became a huge professional and popular success, so they planned the next “yearly exhibition” in the same manner. However, an inner conflict (to put it simply, the antagonism between the abstract and figurative artists) grew into a major political scandal due to a denunciative letter sent to the authorities by some of the board members. As a result, the 1967 exhibition was decimated by a rigorous “outer” jury. Board members were dismissed by the authorities, and the artistic director was fired and even banned from the profession.

În perioada 1964–1975, angajaţii Muzeului Tehnicii Populare din Sibiu au salvat cinci mori de vânt din satele din Dobrogea, aflate în pericol de a fi distruse de programul de modernizare a agriculturii, care a urmat finalizării colectivizării în anul 1957. Un rol cheie l-a avut Hedwig Ulrike Ruşdea, muzeograf şi etnograf al Muzeului Tehnicii Populare, care s-a specializat începând de la mijlocul anilor 1960 în cercetarea morilor preindustriale din România. Echipa Muzeului Tehnicii Populare nu doar a salvat şi reasamblat aceste mori în cadrul muzeului în aer liber din Sibiu, ci a întreprins şi cercetări privind istoria tehnicii morilor de vânt, rolul lor în comunităţile locale, poveşti ale localnicilor legate de aceste artefacte şi de foştii proprietari. Hedwig Ruşdea a fructificat aceste cercetări prin redactarea unor studii despre morile de vânt din Dobrogea. Unele dintre acestea se regăsesc în manuscris în arhiva ştiinţifică a Muzeului ASTRA, precum studiul intitulat: „Morile de vânt din Dobrogea – România: Descriere şi tipologie,” datat în anul 1966. După o scurtă introducere în istoria morilor de vânt în România, Ruşdea analizează evoluţia morilor de vânt din Dobrogea şi remarcă efectele devastatoare ale modernizării rapide a regiunii asupra acestor artefacte, care reprezintă un simbol al patrimoniului cultural al regiunii. Dacă la începutul secolului XX se aflau în regiune peste 740 de mori de vânt, la începutul anilor 1980, numărul lor a ajuns la trei. De asemenea, studiul realizează o tipologie a morilor de vânt în funcţie de structură şi principiile de funcţionare şi compară tehnica morilor de vânt din Dobrogea cu mori similare din alte regiuni ale Europei.

Čolak, Nikola. Struggle goes on: independent Yugoslav intellectuals are not surrendering, in Italian, 1966. Manuscript

Čolak, Nikola. Struggle goes on: independent Yugoslav intellectuals are not surrendering, in Italian, 1966. Manuscript

The collection documents the work of Croatian historian and political émigré Nikola Čolak (1914-1996). In 1966, he belonged to a group of academics and thinkers from Zadar, who officially sought to break the Communist Party's monopoly on truth by establishing the first journal not controlled by the Party. After the suppression of this initiative, Čolak was forced into exile in Italy. The so-called Movement of Independent Intellectuals represented the first attempt to create a formal cultural opposition circle not only in Croatia, but in Yugoslavia as a whole, which is recorded through this collection.