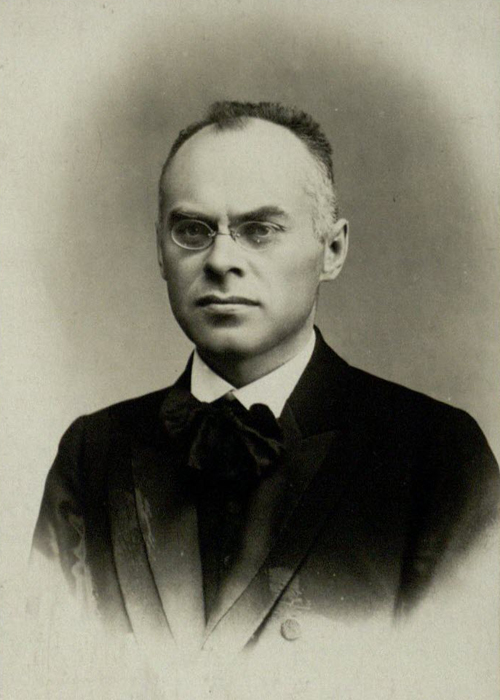

Augustinas Janulaitis was a famous Lithuanian political and cultural activist. He cooperated with the illegal Lithuanian media, and was an active member of the Social Democratic Party. He translated the Communist Manifesto (the first edition, 1904) into Lithuanian. Janulaitis was persecuted by the Imperial Russian government for his political activity, and was obliged to emigrate. For a few years, he studied at Bern University in Switzerland. He returned to the Russian Empire, and graduated in law from Moscow University. During the interwar period, as a well-known lawyer and professor, he shifted to the political right, and published a critical study about Soviet Russia ('Lithuania and Contemporary Russia', 1925.) Janulaitis was known to students, the academic community and the public as a legal and cultural historian. He collected material about personalities who played an important role in Lithuanian history and culture: about the lawyer and historian Ignas Danilevičius (1787-1843), the writer and folklorist Mykalojus Akelaitis (1829-1887), the poet Kiprijonas Nezabitauskis (1779-1837), the cultural historian Simonas Daukantas (1793-1864), and others. Janulaitis wrote and published biographies of Danilevičius and Akelaitis. His studies in Lithuanian culture had a huge influence on students, including Meilė Matjošaitytė-Lukšienė (1913-2009), who became a well-known cultural historian, and at the end of the 1980s she helped to initiate the Sąjūdis movement along with other Lithuanian intellectuals. Janulaitis was the uncle of Meilė Lukšienė.

During the Soviet period, Janulaitis was loyal to the regime. He participated in creating the Academy of Sciences in Soviet Lithuania in 1941, and was elected a member. In 1945, he became the dean of the Faculty of History at Vilnius University. However, in 1946, he was accused of 'bourgeois nationalism' during an ideological campaign that was started by Party authorities against 'Western influences' and 'cosmopolitism'. The Party leadership 'reminded' him of his negative attitude towards Soviet Russia. He survived, but retired from the university and the academy. He died in 1950. Students and the younger generation of the Lithuanian intelligentsia saw him as a representative of the cultural elite of independent Lithuania. His studies in 19th-century Lithuanian culture and his collection of documents about activists in the national revival had a huge impact on Lithuanian historians, especially during the period of the national revival in 1988-1990.