In the middle of the 1980s, Ákos Szepessy and Miklós Tamási, who were high school students at the time, started to search for old photos during clear-out sales as a hobby. Three decades later, Fortepan, the digital photo collection founded by them, has become one of the most important sources and collections on historical photos of the Hungarian press: on average, five articles are published per day with pictures from Fortepan. Despite this, the future of the collection is not certain, in spite of the fact that it has a growing numbers of private users.

Collecting photo negatives was a far more uncommon pastime for intellectuals than searching through clear-out sales in the 1980s and 1990s. However, as Tamási observes, members of the middle class and students began to abandon the practice of searching the clear-out sales as if they were “treasure hunts.” Due to large-scale poverty, more and more people tried to bring in money by selling items, and this sometimes was a source of considerable tension. As a result, the activity itself lost some of its appeal. The widening gap between rich and poor also influenced how the pastime of collecting was pursued, and this makes it harder to preserve this important part of the country’s cultural heritage. The prints stir public interest still today, and they have some market value, but the negatives can be easily lost forever. Back in the day, Tamási set aside at least forty days every year to go to clear-out sales, and he thus amassed a collection of about five thousand items, which later became the basis of Fortepan.

Tamási’s interest in old pictures was partly motivated by the memory of the Revolution of 1956, which by the time he was a teenager had already been blurred by the memory politics of the regime. As he put it in an interview in 2010 with the online portal Mandiner, “For me, the starting point for collecting photographs was the revolution. I was interested in 1956 and curious about the details, few of which were available at the time. This was in 1987–1988, and with the exception of a few blurry pictures in textbooks, visual materials were not accessible. Furthermore, my father was taking pictures in 1956. I saw these pictures in the family albums, and they were very interesting.” After the transition, collecting photos taken during the revolution remained his passion, and motivated by this passion, he managed to get into the storage facility of UVATERV, where the road construction company kept its photo archive (the company documented several large construction projects done from 1949 onwards). This was the first unknown collection of photo material to which he has gained access. He bought a scanner and digitized a portion of the approximately 150,000 items in the collection. More than 4,000 of them are available at Fortepan today. (In 2015, a portion of the burned collection of UVATERV was saved by Fortepan and Mai Manó Ház.)

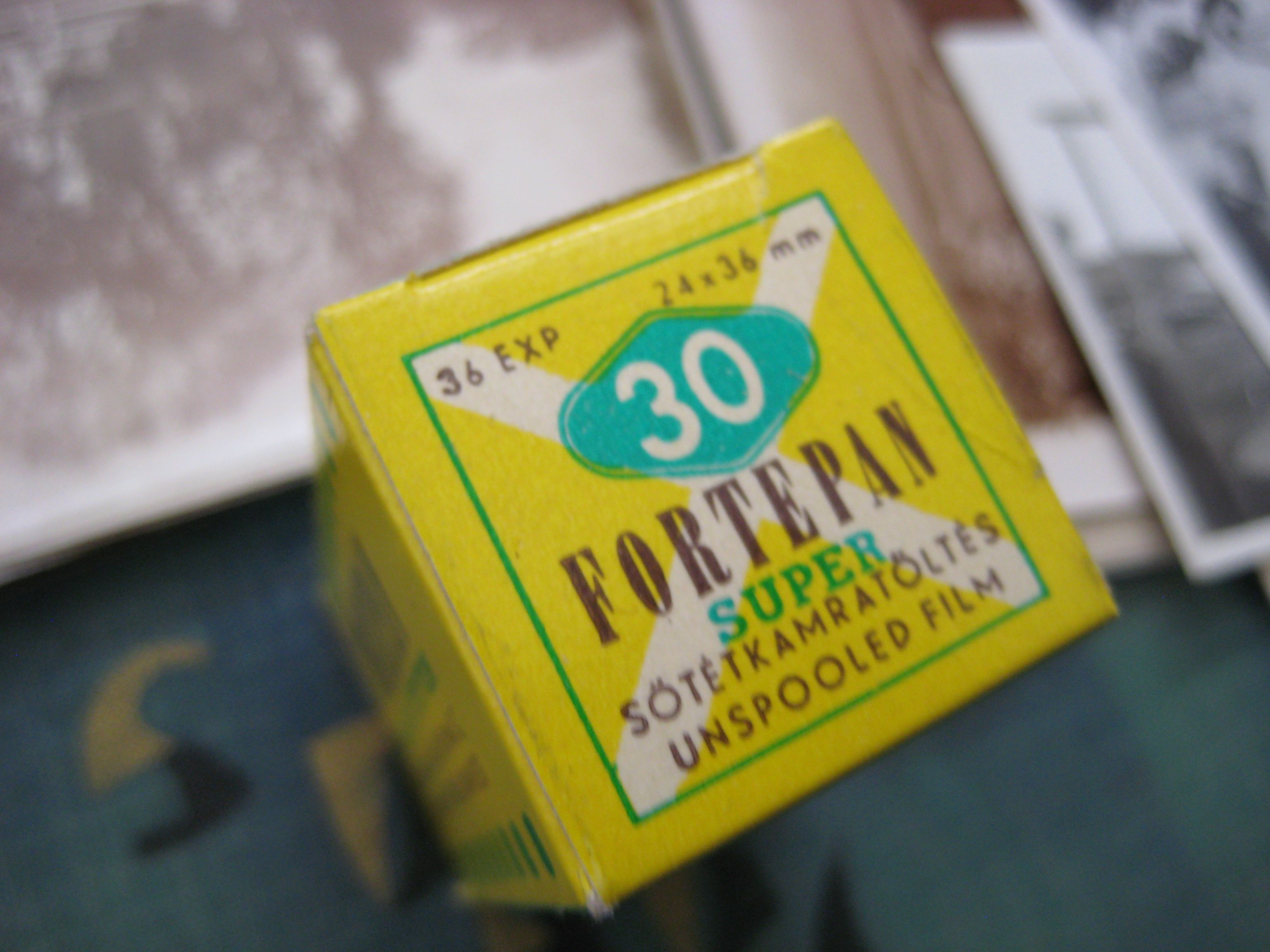

First, before the spread of the internet, the plan was to create albums about the material collected from various places. This attempt came to nothing, because publishers were concerned about copyright issues. In 2009, the people involved started to think about sharing the material digitally. That September, Tamási began to scan the material, so the website could be launched in 2010. The name refers to a former Hungarian photography company, Forte. Fortepan was soon a success and met with considerable attention, as it made a huge collection of photographs available for free. In the first few months, several offers were made: the donations included photo collections and family albums of private individuals and families. The users helped gather data and information about the uploaded pictures from the beginning. Crowdsourcing started to work on its own: as soon as the website started, Gábor Lovas started a forum on Index.hu, which remains active and reliable today. The information provided by the forum is used after the editors of Fortepan have check it. Since 2014, managing keywords is essentially done by users under the supervision of editor Pál Négyesi.

The collection grows by about 15,000 new items each year. While Tamási still goes to clear-out sales, buys bequests, and searches the stands at flea markets for new acquisitions, most of the new material comes from public collections, companies, or private donations. Most of the donations are made by people who have found pictures in inherited or newly bought homes. As people do not want simply to throw these pictures out, they donate the collections to Fortepan. Another typical case is when a deceased family member was an amateur photographer and his or her relatives want like to have the negatives developed. Thus, the cultivation of the collection was a mutually beneficial collaborative act. Public collections are also a frequent source of materials. At first, it was mostly archives that contacted Fortepan, as photos and the negatives were mostly just lying around. Given the success of these collaborative efforts, museums started to follow this example. Finally, works by professional photographers are also found in the collection. In most cases, these photos are lent to Fortepan. Fortepan then digitizes them in exchange for permission to make them publicly available online.

However, Fortepan only makes a portion of the digitized material available. This decision reflects Tamási’s philosophy. Tamási thinks of the collection more as an online exhibition rather than a distant, factual representation of past events. Its purpose is to give an impression, glimpses into the past, as it is seen by Tamási. On the one hand, the pictures have to be of good quality, and they must conform to basic compositional requirements. On the other, they also have to be appealing. This latter requirement, obviously, escapes precise definition and is highly subjective, so Tamási does not share the curatorial tasks with anyone (although he did make one failed attempt to do so). Tamási’s favorite photographic era is the 1930s and the short coalition period in the immediate wake of the Second World War. For him, collecting photos was not just a form of community service, but also a way to escape the grey and alien Kádár era into a more exciting, imaginary world.

For Tamási, the aspect of the history of photography concerns not so much a change in technique as it does a change in politics. He is documenting a world which ended in 1989. Nevertheless, he is aware of the extraordinary importance of the change from analogue photography to digital, and he is open to the idea of expanding the project to the 1990s. However, as he sees it, this would require greater historical distance.

Tamási’s statements shed light on a somewhat contradictory situation. On the one hand, the integrity, efficiency, and appeal of Fortepan comes from his ability to select the pictures using his acumen and insight. When the website was set up, the goal was to make everyday life accessible. Until then, historical photographs that illustrated the period and defined public visual memory were photos of politicians and official events. There were only a few scattered visual traces of the lives of everyday people. As Tamási put it in an interview in 2010, the time has come when “we should see not only the political events and leaders, but also the parallel stories of the homes and families.” While he was successful in this mission, Tamási himself acknowledges that this approach is incompatible with the logic of a public collection which, in principle, should not draw distinctions between sources. Initially, Tamási wanted to create a collection which was not overwhelmed by the tragedies of the 20th century. This was partly a consequence of the found materials as well. Amateur photography, especially in the middle of the century, was a hobby for those who could afford it. These people usually took photographs of things in their immediate surroundings, and most of the material came from the wealthier XII, II, and XI districts of Budapest. However, the nature of the pictures began to change in the 1960s. As Tamási commented in 2010 in a remark made to the online portal Litera, “As the 1960s and 1970s approached, the pictures started to contain more and more depictions of suffering. Usually, we only make reference to these images, but we do not publish them. There are some terribly depressing pictures, with broken homes, families, houses, and souls. These things are also parts of our lives, but as Fortepan is not a public collection, I can choose not to remember them. In this sense, the pictures on the website from the 1970s and 1980s do not reflect reality. This can be justifiably criticized. However, it is not the aim of this collection to document reality precisely. That is what the photo archive of the Hungarian National Museum is for. What we would like to show: there was more to the 20th century than monstrosity.” To some extent, this policy is still part of Tamási’s curatorial activity, and this explains, in part, why he is so wary about having Fortepan under the oversight of a public institution. The independence of the enterprise guarantees its continued success. Because of this, the agreement made in 2015 with the Budapest City Archives is of the utmost importance: while it allows Fortepan to continue to pursue its practices, it also acknowledges the logic according to which public collections function by properly storing the original digitized materials without any selection.

The success of Fortepan and the needs of the community did have some influence on Tamási’s approach, however. The collection has expanded rapidly in some subject areas, and Tamási selects more and more pictures with a grimmer tone. The inclusion of the bequests or oeuvres of professional photographers has modified the previous proportions, as press photos contain more documentation of official events. Nevertheless, these pictures are interesting, and it would be a shame not to make them public. Due to the positive responses, considerations motivated by the notion of public service have also grown in importance over the years. But Fortepan always had a very practical raison d’étre, in addition to the noble cause of preserving cultural heritage: as the people involved in the collection organized an exhibition for the Central Gallery of the Open Society Archives, it became evident how hard it is under the prevailing conditions in Hungary to obtain photographs for these kinds of occasions. Academic researchers also had problems illustrating their books with good quality photographs due to the prohibitively high prices. Fortepan wanted to change this situation, and it did. Indeed, the pictures published on Fortepan have even inspired literary works. Through these works Fortepan, is becoming part of the Hungarian cultural tradition.

Despite these trends, the future of Fortepan is uncertain. Concerning technical questions, storage is not a problem. Until 2015, the data was stored on the servers of Central European University. When the amount of data was so high that storage became a problem for CEU, the photos were transferred to a German server, and the editing of the images is provided by a Canadian server, free of charge. This was made possible with the help of a Canadian Hungarian programmer who finances this service himself. Other IT specialists also offered help, for instance, a young Hungarian programmer developed an iPhone application. Nevertheless, the further expansion of Fortepan is limited financial constraints. A staff is required simply to organize, digitize, and deal with the materials. Work has not even been completed on the materials in the Budapest City Archives, though completion of this work is crucial, especially in the case of negatives. Because BCA only collects paper-based materials, they are not keen to assume responsibility for the negatives. The necessary functional background also needs to be provided for loans of photographers’ bequests and oeuvres, since without this background, it is hardly possible to preserve this part of the country’s and region’s cultural heritage. Over the course of the last few years, work on the project has continued thanks to the generosity of private donors: for example, the owner of a publisher offered to cover one-third of a year’s budget if others would make similar contributions. Companies offered to play similar roles, but they are not providing any support for the core activity, which is mostly done by Tamási (assisted by a little voluntary editorial community), with great personal effort. It will also be necessary, if the project is going to remain sustainable, to attract young people, as most visitors are over 25 years of age. Nonetheless, some three million photos are viewed each month, and 1,200–1,300 people visit the website each day. The agreement with Index about regular thematic compilations also helps a lot with traffic. Currently, Summa Artium Foundation represents Fortepan legally and, sometimes, publicly, and it tries to raise funding for its maintenance and further development.

Lately, Fortepan has also been discovered by users abroad, and it might develop into an international network. In 2015, the University of Northern Iowa started a sister-page called Fortepan Iowa (

www.fortepan.us) thanks to an initiative of the university’s visual communication teacher, Bettina Fabos, who is of Hungarian descent. The American website recently received a huge donation: one of the largest photo collections in the United States, the collection of Michael W. Lemberger, which numbers some 1,500,000 items.