Opanas Zalyvakha's "Zone" ("Zona") is a featured item of the permanent exhibition at the Sixtiers Museum in Kyiv, Ukraine. This painting depicts a crystalline labyrinthine construction, with figures passing in front and outside the enclosure, while others are only able to peer over the tops of volumetric poles, resembling wooden fences that surrounded hard labor camps in Siberia and also the pipes of an organ. Some of these figures blend more readily into the background, while others stand out. The narrow slats between the poles obscure the central figure, who seems to be peering out with eyes downcast and despondent demeanor and is, most probably, a prisoner in the zone. A flurry of figures moves around him in complete anonymity, without the least bit of contact. Art historian Myroslava Mudrak notes that the colors are on the bluish-gray side to underscore the effects of being closed in, and the orange of a setting sun also gives the sense of finality and denouement. The sharp verticality and harsh, repetitive linearity of its component forms gives the painting a sense of tactility—a kind of physicality to the experience of being cut off from everything.Fellow dissident Mykhailo Horyn' considers the verticality of Zalyvakha's paintings to be an indicator of the latter's general philosophy. "There is almost no horizontality to his work...the vertical rays produce a rhythmic-energetic pulse... giving his canvasses a sense of higher meaning and purpose." Another fellow dissident, the literary critic Yevhen Sverstiuk, compares Zalyvakha's approach to that of the poet and political prisoner Vasyl Stus, who always sought "to dig deeper rather than wider." What Stus expressed semantically, Zalyvakha portrayed visually, "hands and forms outstretched, reaching toward the heavens to a higher power, the only force that could defend the individual against tyranny."

Colecția Nelu Stratone reprezintă una dintre cele mai impresionante colecții de discuri de muzică rock, jazz și folk create în România comunistă ca rezultat al combinației fericite dintre neobișnuita pasiune pentru muzica alternativă a posesorului și a abilității acestuia de a achiziționa discuri care nu erau importate oficial. Importanța colecției constă în mărimea ei, dar mai ales în conținutul semnificativ de albume de proveniență occidentală, inaccesibile în magazinele din țară, ce puteau fi însă procurate datorită existenței unei piețe alternative pentru asemenea produse. Realizarea și conservarea unei asemenea colecții erau activităţi privite cu suspiciune de autoritățile comuniste din România, deoarece dovedeau fascinația generaţiei tinere pentru produse culturale occidentale, ceea ce contravenea spiritului Tezelor din iulie 1971.

The collection stores about 250 photos made by Tomasz Sikorski during the Fifth Biennial of Spatial Forms known as Kino Laboratorium (Cinema Laboratory), in 1973. The pictures documented the 1973’s sculptures, objects, and performances, as well as artworks created in the earlier years. There are also some photos from 1972 when Sikorski came to Elbląg to document the preparations for the event. The Biennial, organized in Elbląg from 1965, was one of the crucial neo-avantgarde events in Poland. Cinema Laboratory was the last edition of Biennial in Elbląg; soon after its end Gerard Blum-Kwiatkowski, initiator and founder of the event, moved abroad to Germany.

Acest document este o notă informativă de uz intern redactată de către șeful adjunct al KGB-ului din RSSM, F. Krulițki, și adresată directorului Secției de Anchetă a KGB, A. V. Kulikov. Documentul a fost emis pe data de 26 mai 1972. Acest document a fost produs în contextul intenției exprimate de membrii grupului Usatiuc-Ghimpu-Graur de a trimite un șir de documente create de organizația respectivă la sediul de la Muchen al postului de radio Europa Liberă. Acest post de radio este etichetat drept ”unul dintre instrumentele propagandei imperialiste” care are drept țintă URSS și ”lagărul socialist”. Nota informativă analizează structura organizațională a Europei Libere și subliniază că angajații acestui post ”provin din diverse țări ale Europei de Est (fiind renegați, dezertori, persoane repatriate, trădători de patrie etc. ”). În document se afirmă că cea mai mare parte a bugetului anual al postului de radio Europa Liberă (aproximativ 20 milioane dolari SUA) era constituit din ”subvenții ale CIA”. Este evident că serviciile secrete sovietice erau alarmate de impactul transmisiunilor Europei Libere asupra cetățenilor sovietici. Descriind conținutul reportajelor și al procedurilor operaționale ale postului de radio, funcționarul superior al KGB a subliniat că ”pe parcursul ultimilor cinci ani” (adică după 1967) Europa Liberă și-a intensificat activitățile cu scopul de a ”submina unitatea, coeziunea și prietenia dintre popoarele URSS și cele ale altor țări socialiste, prin ațâțarea naționalismului, provocarea și sprijinirea tendințelor de emigrare și răspândirea isteriei anti-sovietice”. Documentul afirma explcit că între anii 1968 și 1971, transmisiunile Europei Libere acordau o atenție crescândă ”chestiunii basarabene”, menționând frecvent ”așa-numitele pretenții ale României față de teritoriul Moldovei Sovietice și renașterea tendințelor naționaliste în interiorul republicii moldovenești”. Aceste tendințe provocau anumite temeri în rândul funcționarilor KGB, fapt care explică parțial sentințele dure pronunțate împotriva grupului Usatiuc-Ghimpu-Graur și, în general, acțiunile represive împotriva ”naționalismului local” care s-au intensificat pe tot teritoriul Uniunii Sovietice la începutul anilor 1970. Documentul sugerează, de asemenea, sensibilitatea crescândă a funcționarilor sovietici de rang înalt în privința contextului internațional și a imaginii URSS în străinătate.

The first private dance house was opened on 6 May 1972 in the Book Club at Liszt Ferenc Square in Budapest, where Ferenc Novák and his followers showed the simple form of the “széki” dance (Szék, Sic is a Romanian village). The event was organized by dancers of the Bihari Dance Ensemble, Jolán Foltin, Lajos Lelkes, and Antal Stoller. The dancers of the Bartók, the Vadrózsák, and the Vasas Dance Ensembles also took part in it; the music was provided by Béla Halmos, Ferenc Sebő, and Péter Éri. The main supporter of the event was György Martin. He helped Béla Halmos and Ferenc Sebő too. Martin showed them the Collection of Szék by László Lajtha and other records what later became the music collection of the dance house movement. Halmos and Sebő learnt from Sándor Tímár in 1971 how to play music for dancers.

“Music and dance like in Szék” was written on the invitation for the first private dance house in 1972. Opposite the entrance, there was a photo by Péter Korniss who also spent a lot of time in Szék and documented traditional Transylvanian peasant culture. At the door, Lajos Lelkes and Antal Stoller gave the guests a welcome similar to the welcome they would get in Szék. Originally the organizers wanted to reconstruct the traditional dance house of Szék, but later there were also ethnographical and sociological lectures at the dance houses.

In 1972, there were three more private dance houses at the Book Club.

At the end of 1972, Béla Halmos, Ferenc Sebő, and Mihály Sipos traveled to Szék because they wanted to learn about the dance house. Here Béla Halmos heard the band of István Ádám "Icsán,” and he started to learn folk songs from them. In Budapest, when Béla Halmos organized the dance houses, the model for him was the dance house of Szék, where that was a natural event every time.

Over the course of the years, the dance houses in Budapest became more and more popular. Young people had chances to learn and hear about that information and ideas which were not allowed at schools or universities. The HVDSZ, VDSZ, VASAS, ÉPÍTŐK were the main Ensembles at the dance houses. From 1973 the members of the Bartók Dance Ensembles taught folk dances at Fővárosi Művelődési Ház. New folk music bands were founded which resembled Muzsikás, and the dance house movement became popular at all around Hungary.O figură principală a opoziției culturale românești împotriva regimului comunist, Paul Goma, a început să-și scrie cartea Gherla în timpul primei sale călătorii în străinătate (între iunie 1972 și iunie 1973). Titlul se referă la numele orașului transilvănean, unde a fost închis între 1957 și 1958 din cauza încercării sale eșuate de a-i mobiliza pe studenții Universității din București în contextul Revoluției Ungare din 1956. Cartea, care reprezintă o relatare personală a experienței lui Goma ca deținut politic în Gherla, a fost publicată în 1976 și a reușit să stârnească interesul publicului occidental pentru ceea ce s-a întâmplat în închisorile comuniste românești (Petrescu 2013, 124-125, 121).

Gherla ia forma unui dialog pasionat al autorului cu el însuși și se concentrează asupra ultimelor două zile petrecute de el în închisoare. Principalul eveniment din acele zile au fost bătăile atroce pe care Goma le-a primit de la autoritățile penitenciarului din cauza implicării sale într-o dispută între doi deținuți. În consecință, el și un alt prizonier, căruia i-a luat partea împotriva informatorului închisorii, au fost chemați la interogatoriu. Lucrurile au escaladat, iar cei doi au fost torturați de către directorul adjunct al închisorii, sub privirea doctorului închisorii și a altui gardian, recunoscut pentru procedurile sale de tortură. La instigarea ulterioară a informatorilor din închisoare, aceiași doi deținuți au primit o a două bătaie și mai brutală în vechiul sector al închisorii, construit în timpul împărătesei Maria Tereza. În timpul bătăii, la care directorul adjunct al închisorii și gardienii au participat, cu bucurie, încă o dată, naratorul a ajuns la capătul capacității sale de a îndura și, astfel, și-a promis că nu va uita niciodată și că nu va menține tăcerea despre tortura lui.

Episoadele pedepsirii lui Goma sunt relatate cu multe întreruperi și divagații, care contribuie la descrierea contextului mai larg al evenimentelor: înrăutățirea condițiilor din închisori după Revoluția Maghiară din 1956, represiunea nemiloasă a unei revolte a deținuților și creșterea terorii pe care prizonierii erau forțați să o îndure de la torționarii lor, care au învățatdin experiența sovietică. Întreruperile permit incursiuni în viața naratorului înainte de internarea sa în închisoarea de la Gherla, care încep cu perioada în care a fost instructor de pionieri și se termină cu procesul și condamnarea sa.

Dincolo de drama personală a naratorului, cartea Gherla este, de asemenea, o relatare convingătoare privind funcționarea din interior a sistemului penitenciar și a abuzurilor nenumărate, pe care detinuții au trebuit să le suporte de la gardieni și de la alți oficiali ai închisorii. De asemenea, Paul Goma este un observator fin al detaliilor mici și aparent nesemnificative ale vieții de zi cu zi din închisoare, cum ar fi trăsăturile de personalitate, gesturile, reacțiile, răspunsurile, cuvintele pronunțate greșit, diferitele comportamente, care nu doar colorează, dar și tulbură ordinea strictă din închisoare de la Gherla.

In early 1972, the Municipal Conference of League of the Communists of Croatia (LCC) in Zadar appointed a separate working group with the task of interrogating and assessing the political responsibility of 16 party members accused for escalating the “mass movement” in the city of Zadar. As most of the reformist communist leaders at the republic (Miko Tripalo and Savka Dapčević Kučar) and local level (those who were supporters of Tripalo and Dapčević-Kučar), Ivan Aralica resigned from his post as deputy chairman of the Municipal Conference of LCC - municipality of Zadar in the course of December 1971. Although not a single incriminating word was found in his texts and statements, the working group of the Municipal Conference conducted an inquiry and found evidence against him:

A) as a deputy chairman of the Conference of LCC of the municipality of Zadar, Aralica did nothing to prevent nationalist-chauvinist discussions at conferences, he participated in discussions in which he positively emphasized the activities of Matica hrvatska (MH), he did not condemn individual nationalist outbursts, he submitted papers in which he supported the endeavours of the [Croatian] national movement;

B) at the event “Croatia Yesterday and Tomorrow,” he persuaded the organisers to invite the writer Petar Šegedin regardless of his political qualifications; did not see anything negative in the “politicization of the masses,” although it was clear that this was the heart of the ideology of the mass movement;

C) as president of the MH branch in Zadar, he actively participated in its work and in the creation of its policies, and in the establishment of the special committee of MH in Nin and other villages. Although he knew that MH was turning into a political organisation, he positively assessed its work, although he should not have done so as a political leader;

D) he actively participated in the organisation of the event “Croatia Yesterday and Today” together with representatives of the League of Socialist Youth. The political consequences of this event are very well known;

E) he supported the student newspaper Zoranić and those standpoints in line with the mass movement;

F) he was engaged in overcoming the resistance of the editorial board of the weekly Narodni tjednik (People’s Weekly) in order to subordinate them to the attitudes and needs of the political forces in power;

G) he was an active member of the committee to rename streets and squares, which also had political consequences (Aralica 2014, 128-129).

Although the party cell of the organisation where he worked (the Pedagogy Gymnasium in Zadar) did not find any culpability in his actions, the working group concluded that “his contribution to the escalation of the ‘mass movement’ was immense” (Aralica 2014, 129). Because of this, Aralica was suspended from the League of the Communists of Croatia in May 1972.

Juozas Keliuotis (1902-1983) was a famous Lithuanian intellectual in the Catholic movement. He was founder of the journal Naujoji Romuva in 1930, and its editor-in-chief until 1940. After the beginning of the Soviet occupation, he was sent to Siberia as a political prisoner. After his return to Lithuania, the KGB still followed his every move, trying to force him to collaborate with the Soviet regime. Keliuotis refused to collaborate, becoming a well-known figure in the cultural opposition in Lithuania. KGB documents from the collection demonstrate the efforts by Soviet state security to break his anti-Soviet network. The KGB finally succeeded in 1972, and he agreed to make a public denunciation of his past ‘bourgeois’ activity. It was even presented to the Central Committee of the All-Union Communist Party by Yuri Andropov, the head of the KGB of the USSR, as a clear victory against the ‘nationalist intelligentsia’. Keliuotis’ case shows clearly the limits to freedom and self-expression under the Soviet regime. The document is the KGB operational plan for working against Juozas Keliuotis.

Vasyl Stus’ fourth volume of poetry was written under particularly difficult and unusual circumstances, during a nine month period in 1972, when he was held in isolation prior to his trial and sentencing. The poems were written in pencil (as he was forbidden from using pens) into a single notebook from January to September. Despite the austere conditions and near total isolation, Stus himself and literary scholars point to this period as one of explosive creativity in which he wrote nearly 200 poems and 100 translations. This notebook captures not only the circumstances under which these poems were written, but also Stus’ own extraordinary gifts as a poet and his strength of character.

Supravegherea informativă a lui Lucian Pintilie de către Securitate a avut ca rezultat și înregistrarea conversațiilor lui private. Acesta a fost cazul discuției cu actorul Paul Sava, care a avut loc la 15 noiembrie 1972, într-una din sălile Teatrului Lucia Sturdza Bulandra, unde Pintilie lucra. În timpul dialogului, Lucian Pintilie se plânge de faptul că autoritățile culturale românești i-au făcut viața dificilă, încercând să-l împiedice să își continue proiectele cinematografice în Iugoslavia pe motiv că “nimeni nu știa ce avea de gând să facă acolo.” În consecință, fără aprobarea lor, el nu putea obține pașaportul de serviciu, care i-ar fi permis să călătorească și să lucreze în Iugoslavia vecină. Întrebat de Paul Sava de ce nu a vrut să lucreze în România, Pintilie a răspuns că dorește să lucreze acasă și că a abordat deja autoritățile cu un plan de pune în scenă Pescărușul lui Cehov. Cu toate acestea, cenzorii s-au arătat reticenți față de proiectul său, deoarece se temeau de un nou scandal după interzicerea producției sale de teatru după Revizorul lui Gogol în 1971.Pintilie a negat că a avut un fel de agendă ascunsă și subversivă în punerea în scenă a piesei lui Gogol și a ales această piesă deoarece Revizorul reprezenta “crezul său moral și estetic.” El a adăugat că își va folosi contactele personale cu unele dintre cele mai importanți lideri ai partidului pentru a accelera eliberarea pașaportului și a obține aprobarea oficială pentru punerea în scenă a piesei lui Cehov. În acest punct al conversației, Paul Sava a intervenit și l-a întrebat de ce el nu a vrut să accepte nici un fel de compromis cu puterea politică, de ce nu a încercat să înțeleagă “anumite interese, unele puncte de vedere politice,” având în vedere faptul că nimeni nu poate “supraviețui în afara politicii, fără cunoașterea ei.” Răspunsul lui Pintilie conține argumentele care au stat la baza refuzului său de a ajunge la un compromis cu puterea politică și de a i se opune în domeniul culturii. El a menționat că singura politică pe care a înțeles-o era “arta spectacolului prin care slujește poporul.” Paul Sava a continuat și l-a întrebat dacă munca sa artistică ar putea fi numită politică și dacă într-adevăr ea servește intereselor poporului, așa cum pretinde el. Pintilie a răspuns că nu dorea să știe nimic despre politică, deoarece el considera munca sa artistică ca fiind separată de ea. Din punctul său de vedere, Nicolae Ceaușescu era un “geniu politic și se ocupa de politică”și el a avut “geniul spectacolului” și s-a ocupat de el. El a adăugat, de asemenea, că era sigur că liderul comunist român nici măcar nu știa despre munca sa. În consecință, aceia care trebuiau învinuiți pentru interzicerea muncii sale erau activiștii culturali, dispuși să-l mulțumească pentru a evita pierderea funcțiilor lor. Cei doi interlocutori au părăsit teatrul și înainte de a-și lua rămas bun, Sava i-a urat lui Pintilie să câștige “puțină înțelepciune” și să-și reconsidere poziția sa intransigentă în probleme culturale și în relația cu autoritățile (ACNSAS, fond Informativ, dosar 52 vol. 1, ff. 107-110, 111 f-v).

Modris Tenisons’ troupe worked in Kaunas Musical Theatre for only two years, between 1970 and 1972. During this short time, it received many invitations from cultural institutions in other Soviet republics. It is obvious from the documents in the collection that people’s opinions of the performances by the troupe were always high, and theatre managers received many letters about the good and interesting pieces that held the attention of audiences in various places. But the situation changed in the middle of 1972, after the self-immolation of Romas Kalanta and youth protests in Kaunas. In a resolution by the theatre's council, Tenisons and his troupe are accused of leading an un-Soviet way of life. The document makes a reference to the minister of culture Lionginas Šepetys, and says that the troupe had not found its place in the theatre company, and it disseminated strange ideas of bourgeois ideology. Thus, in a very short period of time, we can see a sharp change in opinions about the troupe expressed by theatre managers . The document is the last in the collection. After its dismissal from Kaunas Musical Theatre, no more documents were produced about Tenison's troupe.

The members of Orfeo built a semi-detached house in Pilisborosjenő (15 kilometers from Budapest) between 1972 and 1974, when they wanted to improve the conditions under which they worked. The first house became the home of the actors of the Orfeo Studio. The Orfeo Group constructed a commune, while also holding theatrical and musical performances and creating artwork and photos. The creation of a collection on their work is the result of ordinary activities and an alternative, opposition-cultural lifestyle, which was, in turn, embodied in a house and objects. The inner spaces, the furniture in the house, and the uses of the furniture themselves are artistic works. The houses were spaces of the alternative theatre work and alternative lifestyle of Orfeo, which was condemned by the state authorities as violating the norms and morals of social coexistence.

Inițial, cazul împotriva lui Alexandru Șoltoianu a făcut parte din dosarul mai mare al grupului Usatiuc-Ghimpu-Graur. Șoltoianu a fost arestat la 13 ianuarie 1972, alături de ceilalți protagoniști ai acestui caz. Cu toate acestea, la 29 aprilie 1972, dosarul său a fost separat de celelalte, deoarece autoritățile sovietice nu au găsit dovezi convingătoare privind o legătură directă între activitățile lui Șoltoianu și cele ale Frontului Național Patriotic. Acuzațiile împotriva lui Șoltoianu s-au bazat pe afirmația că „el a întreprins, în mod sistematic, anumite activități organizaționale îndreptate spre crearea unei organizații naționaliste clandestine, cu scopul de a lupta împotriva ordinii sociale care există în prezent în URSS și de a submina puterea sovietică”. O acuzație deosebit de gravă se referea la „răspândirea, în anturajul său imediat, a calomniilor și minciunilor care discreditau statul sovietic și ordinea socială din URSS”, inclusiv prin „producerea, depozitarea și răspândirea unor documente de natură ostilă [puterii sovietice].” Este interesant faptul că acuzația specifică de susținere și propagare a „secesiunii RSS Moldovenești și a unei părți a RSS Ucrainene” din componența Uniunii Sovietice și a unificării acestora cu România nu figurează în mod vădit în acest document. Severitatea deosebită a atitudinii autorităților față de cazul lui Șoltoianu și sentința foarte dură se datorează, în special, intenției sale de a crea o rețea extinsă de rezistență antisovietică, cu obiective etno-naționale clare, care ar fi fost bazată pe recruți din rândul „tineretului studențesc și a intelighenției de naționalitate moldovenească”. Deși materialele anchetei arată clar că cercul partizanilor lui Șoltoianu nu a depășit, cel mult, cincisprezece până la douăzeci de persoane, el a fost pedepsit mai ales pentru intențiile și îndrăzneala planurilor sale neîndeplinite decât pentru rezultatul real al activității sale. Pregătirea academică a lui Șoltoianu în domeniul relațiilor internaționale și în studii orientale a condiționat și sensibilitatea sa deosebită față de literatura istorică, precum și meditațiile sale extinse asupra naturii „coloniale” a relațiilor ruso-moldovenești din interiorul URSS, pe care le-a comparat sistematic cu experiența imperială a Rusiei. În cursul procesului său de judecată, Șoltoianu a încercat să convingă judecătorii că nu a intenționat niciodată ca activitatea sa să fie „antisovietică” sau „anticomunistă”, subliniind că nu a vizat niciodată sistemul în ansamblu, ci doar dominația etnicilor ruși și presupusele politici de discriminare aplicate față de conaționalii săi moldoveni. Se pare, totuși, că motivația etnică a argumentării sale a convins autoritățile de potențialul pericol al activităților sale, având în vedere faptul că naționalismul local a fost perceput ca fiind cea mai serioasă provocare pentru autorități la periferia sovietică. Unele dintre lucrările și opiniile lui Șoltoianu păreau să incite deschis la revoltă împotriva regimului sovietic, în timp ce critica sa deschisă și radicală a politicii externe sovietice (în special a invaziei sovietice a Cehoslovaciei) a completat această imagine. Probabil cel mai îngrijorător element al planurilor lui Șoltoianu a fost, pentru autoritățile sovietice, proiectul său de a crea o rețea extinsă de asociații studențești la Moscova, Leningrad și într-un șir de alte orașe din partea vestică a URSS (Kiev, Odesa, Harkov, Lvov, Ismail, Cernăuți și Belgorod-Dnestrovskii) . „Naționalismul burghez” și „înclinațiile antisovietice radicale” pe care Șoltoianu le-a manifestat în variantele nepublicate ale proiectatului său tratat politic, deși erau destul de grave din punctul de vedere al autorităților, păreau modeste în comparație cu ambițiile sale organizaționale (în ciuda rezultatelor practice extrem de limitate). Discursul pe care l-a ținut în fața unui grup de studenți moldoveni care vizitau Moscova în ianuarie 1963 părea să confirme potențialul pericol al eforturilor sale de propagandă. Actul de acuzare a rezumat cu atenție activitățile „subversive” ale lui Șoltoianu, descriind apariția și creșterea rețelei sale informale și demonstrând, cel puțin apparent, natura gravă a devierilor sale ideologice prin ample citate din fișele sale personale. Actul de acuzare a fost emis la 12 iulie 1972, cu cinci zile înainte de data pronunțării sentinței finale. Acest document dezvăluie nu numai viziunile lui Șoltoianu, ci și ierarhia pericolului perceput și construit de regimul sovietic la periferiile sale „naționale”. Șoltoianu a fost acuzat (și, în consecință, condamnat) conform art. 67, partea I și art. 69 din Codul Penal al RSSM: agitație și propagandă antisovietică / participare într-o organizație antisovietică care urmărește comiterea unor crime periculoase de stat. Agenda lui anti-imperialistă și anti-rusă radicală, chiar dacă era, în multe privințe, similară cu scopurile și strategia grupului Usatiuc-Ghimpu-Graur, era unică datorită sofisticării și ambiției sale.

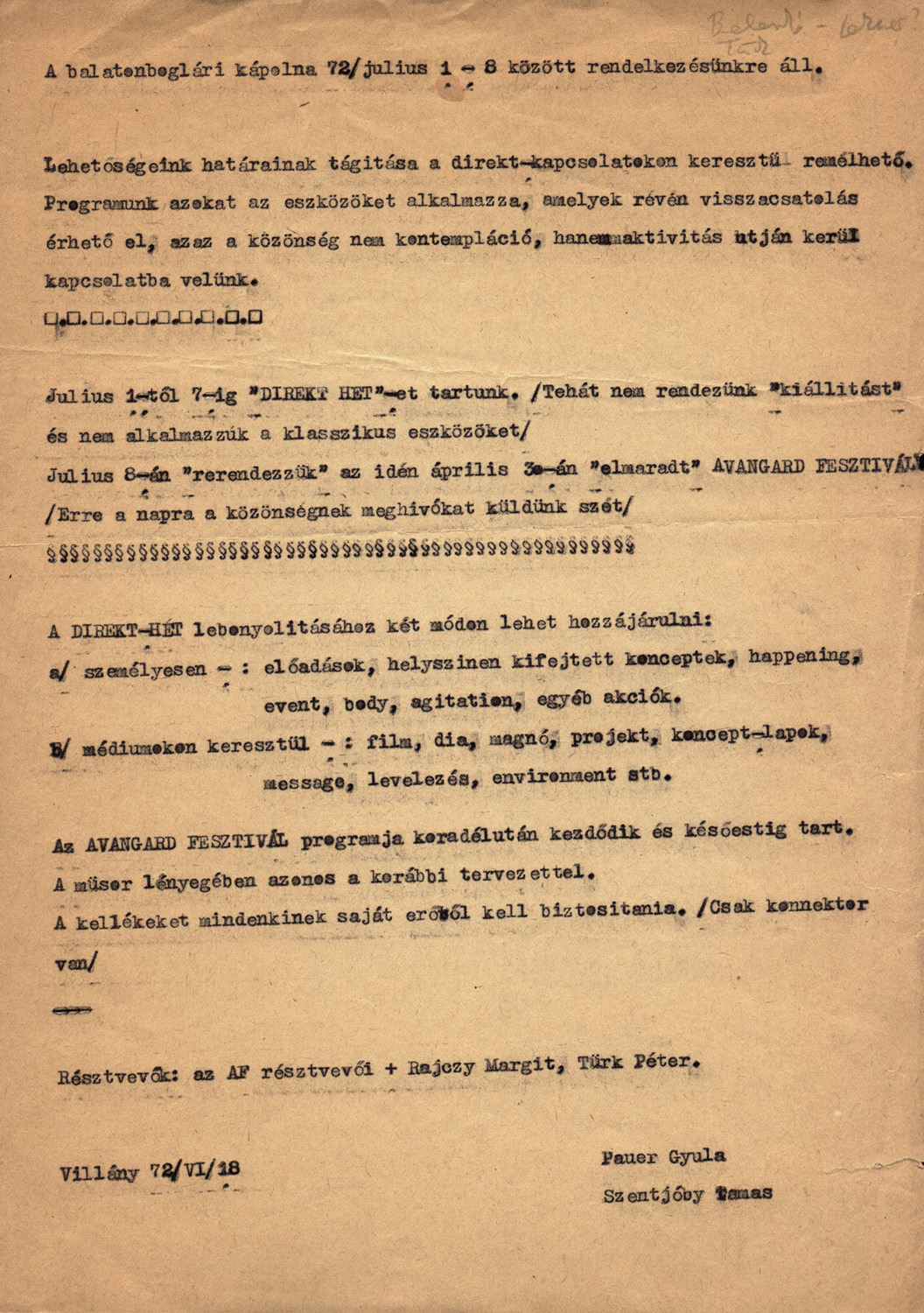

Photo series of spontaneous actions at the chapel: Once we went, May, 1972 (Photo: Dóra Maurer, participants: Miklós Erdély, György Jovánovics, Tamás Szentjóby, Tibor Gáyor)

“There was a grid put across the chapel door, originally from a fence, but applied horizontally and not vertically. Jován stood on it, and the others automatically began to find their places, too. Szentjóby lay down on a branch and stuffed his long hair into his shirt, so his hair was not floating like Jován’s in the photo. Erdély placed himself in the door, bent over, as if he had been glancing out from there, while Tibor lay on the ground, as if that had been another direction, too, and only the smoke of his cigarette revealed which direction was up. Erdély held up a poppy and said that if we photographed it, it might look as if it were the chapel bell. Then they were jumping down from a bench, Erdély, Tibor, and I think Jován, too, as if they were jumping on top of the Badacsony, i.e. as if they had been touching the mountain with the shape of their bodies.” (Dóra Maurer, 1998)

The first private dance house was on 6 May 1972, at Könyvklub at Liszt Ferenc Square in Budapest, where Ferenc Novák and his followers showed the simple form of széki dance (Szék, Sic is a Romanian village). The event was organized by dancers of the Bihari Dance Ensemble, Jolán Foltin, Lajos Lelkes, Antal Stoller. The dancers of the Bartók, the Vadrózsák, the Vasas Dance Ensembles also took part in it; the music was provided by Béla Halmos, Ferenc Sebő, Péter Éri. The main supporter of the event was György Martin who helped to Béla Halmos and Ferenc Sebő too. Martin showed them the Collection of Szék by László Lajtha and other records what later became the music collection of dance house movement. Halmos and Sebő learnt by Sándor Tímár in 1971 how to play music for dancers.

"Music and dance like in Szék” was read on the invitation for the first private dance house in 1972. Opposite the entrance, there was a photo by Péter Korniss who also spent a lot of time in Szék and documented the traditional Transylvanian peasant culture. At the door, Lajos Lelkes and Antal Stoller welcomed the guest like in Szék. Originally the organizers wanted to organize the traditional dance house of Szék, but later there were ethnographical, sociological lectures at the dance houses.

During the year 1972, there were three more private dance houses at the Könyvklub.

The end of the 1972 Béla Halmos, Ferenc Sebő, Mihály Sipos travelled to Szék because they wanted to learn about the dance house of Szék. Here Béla Halmos heard the band of István Ádám "Icsán” and started to learn folk songs by them. At Budapest when Béla Halmos organized the dance houses, the idol for him was the dance house of Szék where that was a natural event every time.

During the years the dance houses at Budapest became more and more popular where the youth had possibilities to learn and hear about that information and interest which were not allowed at school or universities. The HVDSZ, VDSZ, VASAS, ÉPÍTŐK were the main Ensembles at the dance houses. From 1973 the members of the Bartók Dance Ensembles taught folk dances at Fővárosi Művelődési Ház. New folk music bands were founded like the Muzsikás and the dance house movement became popular at all around Hungary.

A diagram The Stages of the Evolution of Art from 1972 is a graphic extension of the idea which Ludwiński presented two years earlier in the text Art in the Post-art Epoch. Ludwiński often used images and diagrams to better explain his thoughts on history and future of art. As a man of a spoken word, he rarely wrote and rather talked, discussed, and argued in an oral way, helping himself with some notes and sketches. On the other hand, Ludwiński’s drawings are a testimony for his visual imagination. In this case, the evolution of art is presented through overlapping of next rings, analogically to the rings visible in the tree’s section.

The Stages of the Evolution of Art in a suggestive way show the dependencies and development directions between the main genres in the modern art, as well as design its forthcoming tendencies, through the conceptual and impossible art (thus the streams developed at the turn of the 1960s and the 1970s, all to the phase 0, when art is supposed to disappear in the reality of science, technology, and social life, acting through empathy and over-intellectual understanding).

Diagram is a repository of Zacheta Lower Silesian Fine Arts Association in the Modern Museum Wroclaw and it is presented on the exhibition in two languages: the original (Polish) and in English translation.

Catholic newspapers published underground were a well-organised and conceptually grounded form of samizdat. The collection consists of two underground publications: Lietuvos Katalikų Bažnyčios Kronika (The Chronicle of the Catholic Church in Lithuania) and Rūpintojėlis (The Sorrowing Christ). The Chronicle was the longest-surviving samizdat publication in Soviet Lithuania, providing alternative news to that coming from Soviet institutions. It was initiated by a group of Catholic priests; while Rūpintojėlis was a publication from the Catholic community that became known for being intellectual and cultivated. The collection is made up of several sources: the Lithuanian Special Archives, which holds issues of the Chronicle of the Catholic Church in Lithuania and Rūpintojėlis confiscated during KGB searches; and the internet page http://www.lkbkronika.lt/ containing digitalised issues of the Chronicle, with comments and introductions.

Colecția Ion Monoran documentează profilul intelectual al unuia dintre liderii mișcărilor culturale underground din Banat, care a devenit, datorită capacității sale de a cataliza acțiunea mulțimii adunate pe străzile Timișoarei pe 16 decembrie 1989, una dintre personalitățile marcante și incontestabile ale Revoluției Române.

This picture shows the honorary diploma given to Hristo Ognyanov by Pope Saint John Paul II in 1981 on the occasion Ognyanov’s 70th birthday and in gratitude for his activities defending freedom of religion (Source: CSA, F. 1264). It is associated with the History of the Bulgarian Church, written by Hristo Ognyanov for broadcasts on Voice of America in the period 1953–1957 (CSA F. 1264, op. 1, a.e. 249–251). In this and in programs on Radio Free Europe, Ognyanov critically discussed communist propaganda against religion. Ognyanov’s program "Eleven Centuries of Christianity in Bulgaria" received an award by The Catholic Broadcasters Association of America. Under the name "Religion and Atheism in Bulgaria under Communism," he delivered a series of lectures in 1974. In Bulgaria, Ognyanov's activities, including those on religious subjects, were considered by the authorities as "subversive propaganda".

Cardboard box with a large, red, stenciled, symmetrical question mark on the outer top of one side and the inner bottom of the other side. On the outer back side, a series of ten photos arranged in a grid demonstrating the possible combinations of similar boxes in an open and closed state.

On the third photo the box on the left is marked with an arrow pointing to a handwritten caption reading “that is this box.” Under the photo appears the typewritten title of the work and the following sentence: “The aim of the experiment is to examine the sensory and esthetic effects of generally asked questions.” Beside the photos, above the label the typewritten name of the author is visible.

The handwritten commentary suggests that a box can be interpreted alone as well (this concrete example incorporates two differently positioned, painted question marks). Looking at the photos, one can conclude that more—though not necessarily identical—copies exist, which were given away (as this example got to the archive).

Politics did not constitute the primary context of Péter Türk’s oeuvre, but a subtle, sometimes ironic, criticism of the system can be observed in his works produced during the first half of the 1970s. During this period, he created geometric, but more and more conceptually oriented works, pursuing visual, semantic-logical investigations, which formed an implicit statement in the eyes of cultural politics at the time.

The question marks appearing in several series of his works are “visual conundrums,” which come into play via their color, position, material, constellation and, last but not least, their variations. Contemplating the object, the viewer becomes involved in a conceptual-associative process.

During our visit, we first wanted to define what is a generally asked question. According to professor Beke, “how are you?” or rather “what’s up?” is a good example. Hearing (or reading) a question of this type it is worth noting that this still concerns the sensory effect.

The object bears the marks of time and the consequences of its storage conditions. Dedicated wood crates or humidity control could not be provided for an item kept in a private archive, but it did not lose any of its authenticity and conceptual clarity even in its current condition.

Usatiuc-Ghimpu-Graur (Frontul Național Patriotic) - Colecția de la Arhiva Națională a Republicii Moldova

Usatiuc-Ghimpu-Graur (Frontul Național Patriotic) - Colecția de la Arhiva Națională a Republicii Moldova

The cantata Lenini sõnad (Lenin's Words) is a purely ironic work. It was formally dedicated to the 50th anniversary of the Soviet Union. Tormis used extracts of texts by Vladimir Lenin. The irony lies in the fact that these were extracts which demanded equality between nations and the right of self-determination. Since the author was Lenin himself, the authorities could not blame Tormis for anything. Whether the authorities understood the irony or not remains unknown. It has not been widely performed, and even not at all since the restoration of independence, but it is often quoted in the press as a curious case. This cantata is definitely not forgotten. For example, Lenini sõnad was one of the works mentioned in the obituaries of Tormis. The original manuscript and a later written copy are currently stored in the Estonian Theatre and Music Museum.

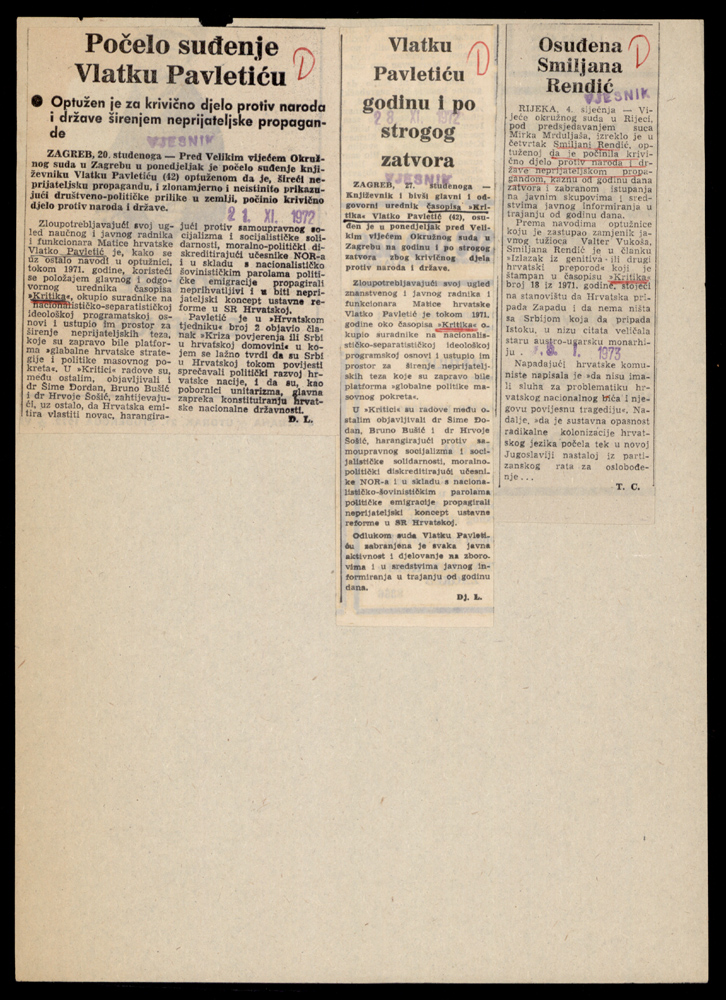

Novinski izvještaji o sudskim postupcima zbog krivičnog djela protiv naroda i države neprijateljskom propagandom, Vjesnik, 1972. – 1973. Novinski isječak

Novinski izvještaji o sudskim postupcima zbog krivičnog djela protiv naroda i države neprijateljskom propagandom, Vjesnik, 1972. – 1973. Novinski isječak

The card contains three cut and glued press clippings containing reports on trials for “offences against the people and the State by enemy propaganda.” As a criminal act aimed against the people and the State, enemy propaganda was defined in the 1951 Criminal Code as propaganda by illustration, writing, or public speech at rallies or otherwise, aimed against the state structure and social system, and against political, economic, military or other important institutions of the people’s government. Strict imprisonment was stipulated as punishment for the perpetration of such a crime.

Two press clippings refer to trials against Vlatko Pavletić (Zagreb, 2 December 1930 – Zagreb, 19 September 2007), the then editor-in-chief of the magazine Kritika, a publication of the literary organization Matica hrvatska and the Croatian Association of Writers. The third clipping refers to a trial against journalist Smiljana Rendić (Split, 1926 – Trsat, 1994), because of her article “Izlazak iz genitiva ili drugi hrvatski preporod” [‘Exit from the genitive or the second Croatian revival’], published in 1971 in the issue no. 18 of the same magazine, which was therefore banned. Together with a group of officials of Matica hrvatska, Pavletić was arrested in 1972 and then sentenced to a year and a half of strict imprisonment as a Croatian nationalist on charges of “attempting to overthrow and alter the state structure.” Rendić was sentenced to a year’s imprisonment and was banned from public activity for one year after her release. They demonstrate a number of cases of prosecution against members of the Croatian Spring that followed the suppression of that reform movement in Croatia at the end of 1971. A significant part of this prosecution encompassed cultural institutions and humanist intellectuals. The work of Matica hrvatska and its magazine Kritika were banned by the communist authorities. The collection includes a number of press clippings about these events, grouped in several topics in the categories for Culture (filing folders KUL 320 and KUL 491) and Domestic affairs (filing folder UP 27 and UP 28), and in the dossiers Public Persons category. The documents are available for research and copying.