În această scrisoare, Emil Cioran reacţionează la veştile primite de la părinţii săi, care i-au scris despre condamnarea fratelui său Aurel Cioran de către un tribunal militar pentru faptul că fusese un susţinător al Legiunii Arhanghelului Mihail. Ca urmare a acestei sentințe, acesta şi-a petrecut următorii şapte ani în închisorile politice ale României comuniste. În acest context, Emil Cioran se raportează critic la implicarea sa şi a fratelui său în activitatea Legiunii. Importanţa documentului rezidă în faptul că ne demonstrează că a existat totuși o instrospecţie critică prin care Emil Cioran a reevaluat implicarea sa în acţiunile Mişcării Legionare. Emil Cioran şi-a exprimat cu această ocazie dezamăgirea că fratele său a continuat să susţină Mişcarea Legionară după 1945. A afirmat că această mişcare politică a adus doar “nefericirea” susţinătorilor ei şi a spus că l-ar fi prevenit pe fratele său despre posibilele consecinţe ale continuării implicării sale în activitatea mişcării. Emil Cioran și-a încheiat această argumentaţie prin afirmația: “Iată unde duce o fidelitate absurdă.” Oricum, Emi Cioran însuşi a fost un susţinător al Legiunii cel puţin până în anul 1941. Evaluarea critică a fostelor sale simpatii politice a fost un proces gradual, care a avut loc după 1945 (Zarifopol–Johnston, 10). Pe lângă valoarea documentară a acestei scrisori, textul are şi o valoare literară în sine. Stilul inconfundabil al lui Emil Cioran este recognoscibil în unele fraze precum: “Viaţa-i o comedie sinistră inventată de Diavol.”Luând în considerare situaţia tragică a familiei sale, Emil Cioran s-a simţit jenat să scrie despre succesul său editorial din Franţa şi a început partea a doua a scrisorii prin a prezenta aceste veşti ca un fel de consolare pentru părinţii săi. Era vorba despre publicarea primei sale cărţi în limba franceză, intitulată: Précis de décomposition. Această carte a fost publicată la editura Gallimard în 1949 şi un an mai târziu a primit premiul literal Rivarol. Această parte a scrisorii vorbeşte, de asemenea, despre dificultăţile întâmpinate de Cioran ca scriitor străin în încercările sale de a se integra în mediul literar francez şi de a se scrie într-o altă limbă decât cea maternă.

The extensive Czechoslovak Writer Publishing House Collection deposited in the Museum of Czech Literature illustrates the publishing activities of one of the most important postwar Czech publishers from its establishment in 1949 until its end in 1997. The materials allow for the reconstruction of the negotiations between authors, editors and publishing managers, and it frequently provides the only evidence of literary works that were never published. This collection provides a picture of censorship in socialist Czechoslovakia and how the publishing industry functioned under a Soviet-style communist dictatorship.

The diaries are presented in the form of separate notebooks which were written by Milan Jelínek over a continuous, yet not daily, period of time. Jelínek recorded his everyday impressions, commenting on current events; a large part of them are summaries and short reviews of the books he read. The diaries prove the mindset of an enthusiastic Communist transformed to a critic, and the disappointment of the social and political development following the Prague Spring. There a also very valuable and non-encrypted, "uncensored" records about the publishing of samizdat titles and the organisation of the underground university within the activities of the Jan Hus Educational Foundation. What is interesting, are also the characteristics of other people from the academic and dissident environment.

În prima decadă a regimului comunist din România, sistemul de educaţie a fost transformat în mod radical prin prevederile legii învăţământului din 3 august 1948, care a impus naţionalizarea şcolilor confesionale. Ca urmare, conducerea Bisericii Evanghelice C.A. a cerut pastorilor să predea ore de religie în vederea confirmării în case parohiale, biserici sau şcoli publice pentru a substitui pierderea şcolilor confesionale. Începând cu a doua jumătate a anului 1948, autorităţile locale au primit instrucţiuni să obstrucţioneze predarea acestor ore de religie în vederea confirmării. Ca reacţie la măsurile autorităţilor, conducerea Bisericii Evanghelice a trimis numeroase memorii Ministerului Cultelor. Episcopul evanghelic Friedrich Müller avea deja experinţa opoziţiei faţă de mişcarea nazistă din rândul minorităţii germane din România. În anul 1941, episcopul Müller s-a opus preluării şcolilor confesionale ale saşilor transilvăneni de către Grupul Etnic German, organizaţie politică controlată de mişcarea nazistă locală. Orele de religie pentru confirmare erau foarte importante pentru Biserica Evanghelică deoarece, fără prezenţa la aceste ore de religie, tinerii nu puteau să promoveze examenul de confirmare şi să devină membri cu drepturi depline ai comunităţii religioase. Pe de altă parte, autorităţile comuniste percepeau aceste ore de religie ca un subterfugiu folosit de biserică în vederea conservării influenţei sale în societate.

De un interes deosebit este memoriul trimis de Consistoriul Superior al Bisericii Evanghelice C.A. din România Ministerului Cultelor în 28 februarie 1949. În acest memoriu, episcopul Müller a criticat măsurile luate de Securitate şi Miliţie împotriva orelor de religie pentru confirmare în satul Brădeni/Hendorf (judeţul Sibiu). Acest document este remarcabil datorită argumentării teologice complexe privind importanţa acestor ore pentru tineretul evanghelic. În prima parte a memoriului, episcopul Müller a argumentat că instrucţiunile trimise secţiilor locale de Miliţie de către Direcţia Regională de Securitate Sibiu încălcau legile statului comunist, inclusiv constituţia comunistă a României din 1948 şi articolul 7 al Decretului 177 din 1948 privind activitatea cultelor religioase. În acest al doilea act legal, explica episcopul, se stipula explicit: “Cultele religioase sunt libere să se organizeze şi pot funcţiona liber dacă practicile şi ritualul lor nu sunt contrare Constituţiei, securităţii sau ordinei publice şi bunelor moravuri”. În plus, episcopul Müller sublinia că interzicerea acestor ore de religie viola drepturile fundamentale ale cetăţenilor, garantate de articolul 27 al constituţiei din 1948. Episcopul invoca într-un mod abil poziţia ministrului educaţiei din acea perioadă care afirmase despre cultele religioase într-un discurs publicat în ziarul oficial Scânteia că acestea erau libere să predea principiile credinţei lor tinerilor. De asemenea, ministrul afirmase că “insultele” la adresa “sentimentelor relgioase” îi ajutau doar pe inamicii noului regim. Invocând acestă declaraţie oficială, episcopul îşi încheia argumentarea cu concluzia: “Nu se poate închipui o jignire mai mare a sentimentelor religioase, decât oprirea învăţământului religios [...] pentru copii şi tineret.” Astfel, episcopul Müller solicita Ministerului Cultelor să facă presiuni asupra conducerii Ministerului de Interne să înceteze obstrucţionarea orelor de religie în vederea confirmării. În acest mod, conducerea Bisericii Evanghelice încerca să profite de contradicţiile politicilor regimului comunist care dorea, pe de o parte, să limiteze influenţa bisericilor în rândul tinerilor, iar, pe de altă parte, să coopteze bisericile protestante.

Nikola Tanev was a Bulgarian painter who studied at the Paris Academy of Decorative Art. Tanev had 28 independent exhibitions in Bulgaria and 27 exhibitions in various European countries: Berlin, Innsbruck, Mannheim, Frankfurt am Main, Hamburg, Leipzig, Stuttgart, Rome, Milano, Amsterdam, Stockholm, Malmö, Warsaw, Prague, Brno, Budapest, Bucharest, Belgrade, Zagreb, Split. He was among the founding members of the Native Art Society. There is no evidence that he was involved in political activities and party and political struggles before 1944. He was not a member of any political party and organization. His elder brother Stefan Tanev (March 15, 1888 – 1952) who was also non-party related was a long-time editor-in-chief of the Utro [Morning] Newspaper (1911 – 1944).

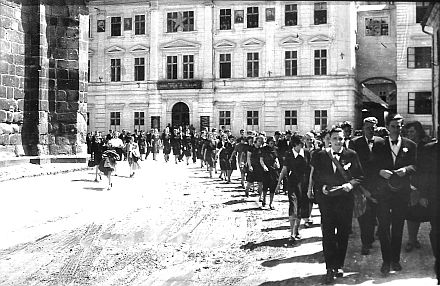

Both brothers were arrested in September 1944 by the so-called "people's democratic power". Stefan Tanev was arrested on September 13, 1944 and sentenced by the so-called People's Court to life imprisonment. In 1952, he died in prison under obscure circumstances. Nikola Tanev was arrested on September 26, 1944 and spent six months in the Central Prison and various buildings adapted for prisons for "political criminals". The intellectuals prevailed among the criminals; there were many painters arrested: Rayko Aleksiev, Aleksandar Bozhinov, Boris Denev, Konstantin Shtarkelov, Aleksandar Dobrinov. After September 9, 1944, the authorities used as a reason for repressions the works of the painters and the reports against them. A joke of the painter Aleksandar Bozhinov from the time he was in jail is preserved: "It is an honour and pleasure to fall among such an intellectual elite! No serious intelligentsia left outside." Tanev as well as the other painters continued their work in the prison; they drew on wrapping paper, on sheets of paper from grocer's books, on accounting forms etc. There are numerous prison sketches, portraits and drawings of the interior of the cells preserved which are of great documentary value.

Nikola Tanev was released from prison in April 1945 with the explanation that he had been imprisoned by mistake. In this period, the painters were openly given propagandist assignments: to approve through their art the "activities of the people's power" and to contribute to the building of socialism. "The period from 1944/1945 to 1955 was extremely important for the development of communism – the socialist realism got its way and the accusations of "formalism" intensified. The "pure landscape" was not in position to solve such tasks thus it was declared unimportant. In documents from the sessions of the art juries one could see the arguments for the rejection of paintings of Nikola Tanev. For example: "The landscape is too relative... This is not an artistic work. I am against its acceptance." (with reference to his painting "Slaveykov Square").

Experiencing the sanctions of the authorities, in order to survive, N. Tanev deliberately decided to take part with his art in the process. However, the differences in relation to Tanev's previous landscapes are significant: the sunny multicolouredness and the jubilant feeling were replaced by distressing autumn and winter pictures; heavy and leaden sky; drizzly; denuded trees; small grey figures. Grey-brown monochromy oppresses everything. A bright example are the miner's compositions of Nikola Tanev. Praised by the state art critique who saw in them a "new stage in his creative work" that approved the "building of socialism" (Божков 1956: 22), these paintings of Tanev show the dark conditions of work in the mines near the town of Pernik which functioned as forced labour places.

In 1949, Nikola Tanev had an apoplectic stroke and two years later – a myocardial infarction. Semi-paralysed, in 1955 he was awarded "honoured painter", a title related to small monthly subsidy which enabled him to take treatments. Nikola Tanev died in 1962.

After the political changes in 1989, the life and work of Nikola Tanev became a subject of many analyses. His art is considered an organic part of the European art but at the same time related to the national way of life.

Until the exhibition "Forms of Resistance" there were no documents published related to Nikola Tanev's stay in prison and there was no connection made between his paintings "Pernik Mines" and the series "Kutsiyan", on the one hand, and his life in prison, on the other hand.

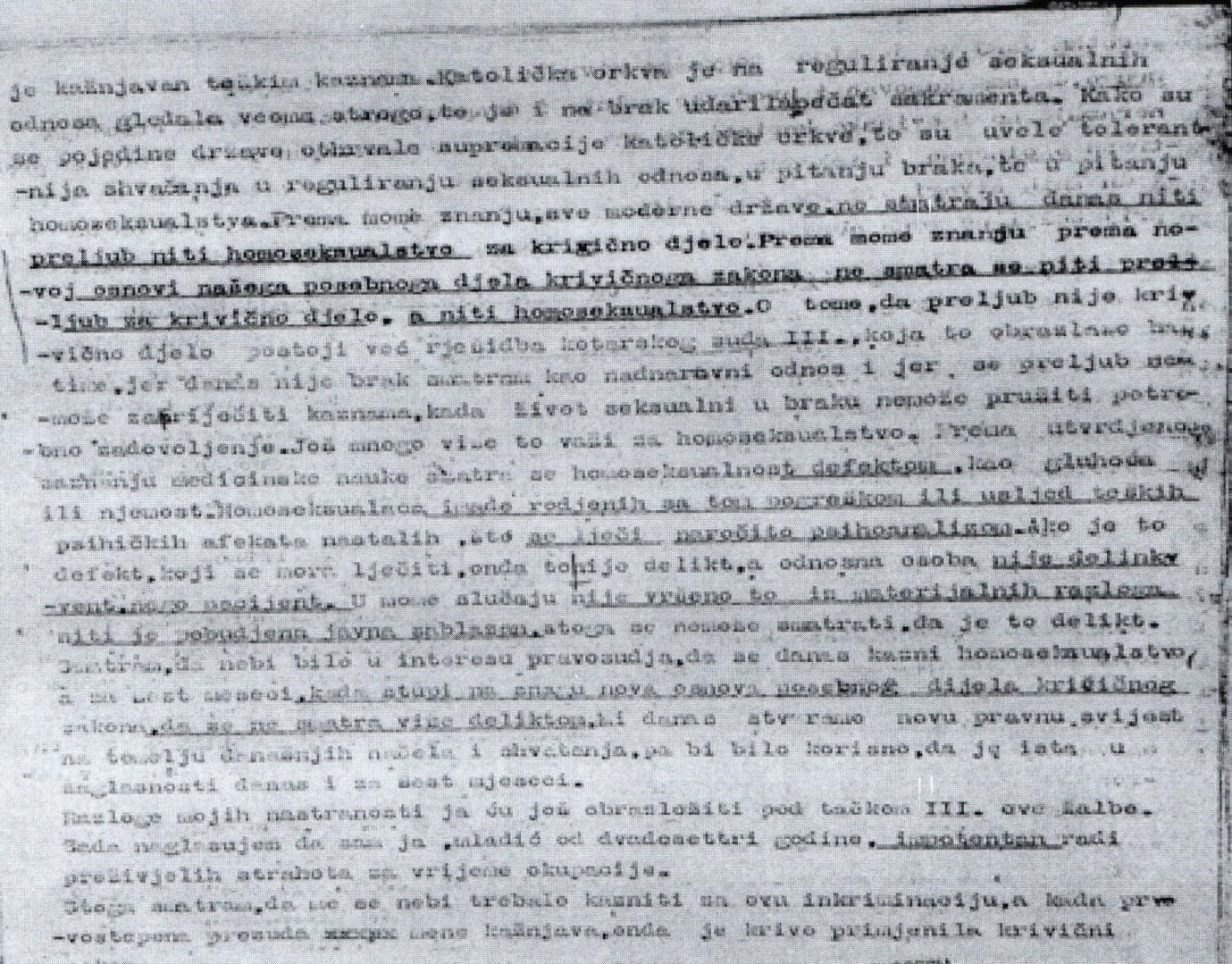

![Croatian State Archives in Zagreb: HR-DAZG-1007-527: “Žalba na presudu Okružnog suda u Zagrebu K 236/949-7” [Appeal letter against Zagreb District Court verdict K 236/949-7], December, 1949.Photo by Franko Dota](/courage/file/n231185/Appeal+letter.jpg)

“I have been sentenced to 6 months in prison for unnatural fornication. I do not believe my behaviour should be punishable by law since it does not constitute a crime. From the most ancient times of human history, among the oldest civilizations, the Egyptians, Greeks, Persians, in the Islamic world, in Japan and China, this ‘unnatural fornication’ had been tolerated. It was only with the emergence of the Catholic Church and its supremacy that this fornication was proclaimed the sin of Sodom, and harshly punished […] Countries that managed to wrest themselves free from Catholic supremacy introduced more tolerant regulation of sexual matters, regarding marriage and even homosexuality. As far as I know, there is not a single modern state that would consider adultery or homosexuality crimes” (HR-DAZG-1007-527: “Žalba [Branka Vujaklije] na presudu Okružnog suda u Zagrebu K 236/949-7”, prosinca 1949. [Appeal (of Branko Vujaklija) against Zagreb District Court verdict K 236/949-7, December, 1949]).

With these words Branko Vujaklija, a 23-year-old theology student and Serbian Orthodox cleric from Zagreb, attempted to convince the Croatian Supreme Court to release him from prison where he was held for “unnatural fornication.”

During his trial, Vujaklija unapologetically declared he was homosexual. He tried to explain to the judge that he was only acting in accord with his “natural sexual instincts,” that his sexual relations were always with consenting adults and never in public, so therefore, Vujaklija argued, he could not have been declared guilty. The judge ignored his arguments, and found his acts extremely immoral (Dota 2017, 94-95). Vujaklija did not give up and wrote an appeal (part of which was quoted earlier). He changed his argument: since he was sentenced as a moral degenerate and a debauched bourgeois, this time Vujaklija himself decided to use ideological arguments as well. He tried to explain to the judges that the contempt towards homosexuality had its origins in the Catholic tradition that should have no place in a new, modern and progressive socialist society. However, his efforts were in vain, and the Supreme Court of Croatia rejected his appeal (Dota 2017, 95).

Both the court sentence and Vujaklija’s appeal were retrieved during Domino’s research, and thus became part of the Collection History of Homosexuality in Croatia. The 1949 verdict, as well as other related documents, including the cited appeal letter, were originally held in the State Archives in Zagreb (DAZG), and are part of the Zagreb County Court Fund (HR-DAZG-1007).

These documents testify to the ideological motivations behind the persecution of homosexuality in the post-revolutionary phase of communist Yugoslavia, but also to the resistance mounted by some sentenced homosexuals against the authorities. Vujaklija was bold and daring enough not only to depict his homosexuality as a completely natural phenomenon, but also to demand his own acquittal and the decriminalization of the same-sex sexual relations in general.