The multiethnic, multilingual, and multicultural world of the French Foreign Legion, that throughout its almost two century long past has recruited its volunteers from among 150 nations, is well reflected by the manuscript “The Slang Vocabulary of the Legionnaires,” edited by Sándor Nemes, a Hungarian veteran residing in Course for close to 50 years now. It provides an authentic insight into the odd group identity of its many Hungarian recruits throughout the twentieth century. To better understand this, one needs to become acquainted with some basic facts of the Legions’ history. The French Foreign Legion, founded in 1831 by King Louis Philippe in Algeria, is still an active and legitimate French armed force, today with some 9,000 mercenaries, that still preserves much of its traditions, although since the 1960s it has been transformed from an old-fashioned colonial army into a modern elite force specialized for international missions of peace maintenance, humanitarian and anti-terrorist tasks, both in France and worldwide.

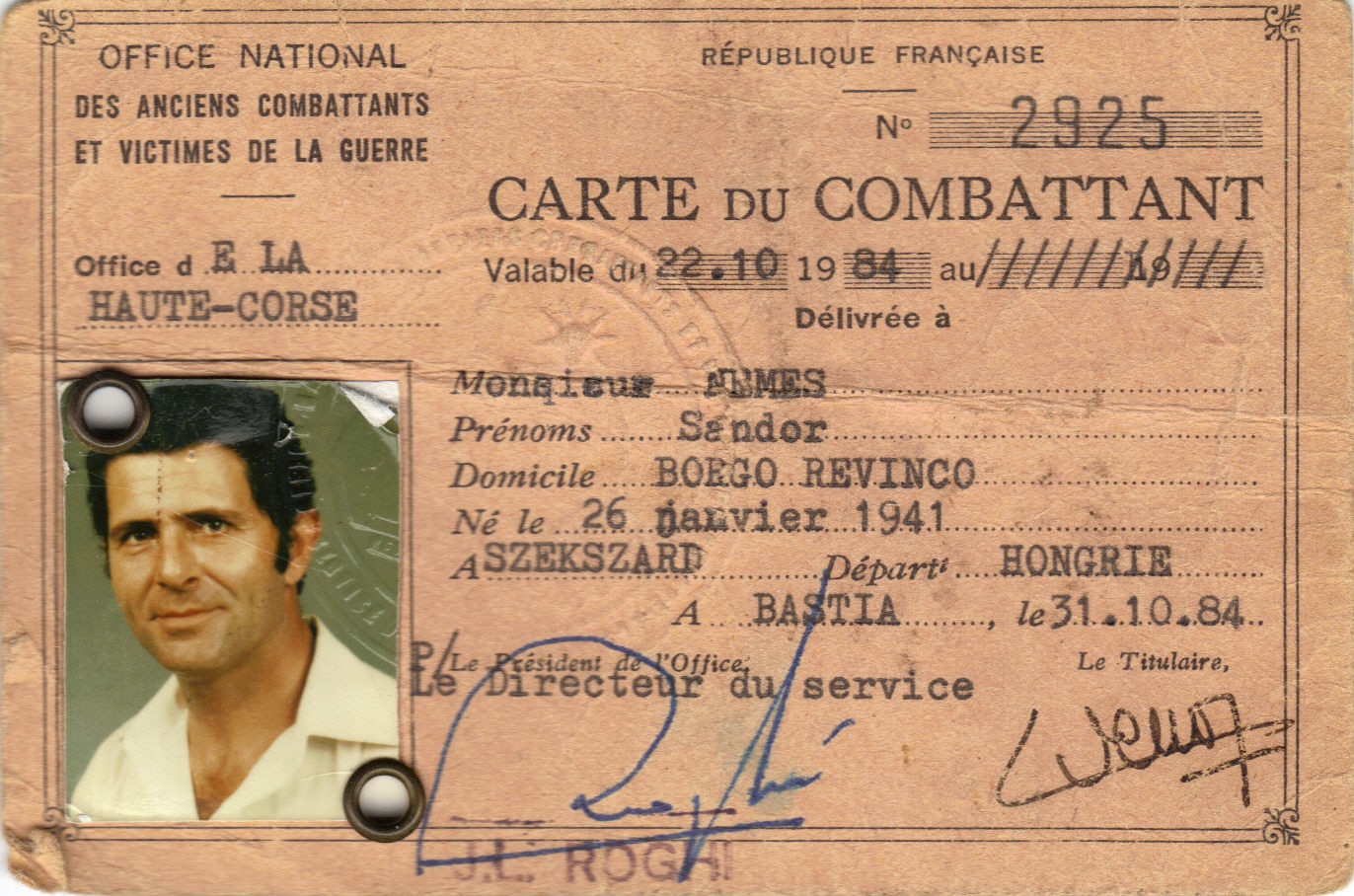

Ironically enough, the French Foreign Legion, due to several grave economic, political, and war crises, preserved for more than a century the traditional dominance of its German-speaking recruits (from Switzerland, Austria, Germany, and elsewhere), who left behind far-reaching effects even on the language use of the Legion’s command and its folklore, e.g., the military marches, which all used to be German songs. Therefore, it is not at all surprising that following 1945 and 1956, when more than 4,000 Hungarians joined the Legion, this newly arrived ethnic group also began to strengthen its cohesion against the challenging dominance of the “German mafia,” as Sándor Nemes and his fellow Hungarian veterans recalled in their accounts. This was, of course, but a limited and rather informal rivalry given the strict hierarchy and the wartime conditions (in Indochina, and Algeria!). Still a “two-front” cultural resistance emerged ever more markedly among the Hungarian volunteers, on the one hand against the mostly native French officers, and the German warrant officers on the other. In fact, at a closer look the Hungarian recruits (who were called “Huns,” “kicsis,” or “Attilas” in the common slang used by the Legion) were not homogenous either, especially as far as their cultural and political identity was concerned. Although the age difference between them was hardly more than 10–15 years, they belonged to two markedly different generations: the ’45-ers, or the “Horthy’s hussars,” recruited mostly from POW and refugee camps after the end of WWII, and the ’56-ers, who fled to the West when the Hungarian revolution was violently suppressed. The main difference between the active ’56-ers and the rest of the Hungarian legionnaires could be felt most in their attitudes and group identity, since the former were much more united in their common engagement in the revolutionary events and battles that they experienced as very young men or even minors. As members of the Hungarian veterans’ circle in Provence, they were the ones who kept in contact for decades and preserved the memory of the revolution up to the present day with their special group rituals (like banquets, memorial meetings, and the sharing of their revolutionary experiences and relics).

These can be best illustrated with a number of funny, original, and telling entries in Sándor Nemes’s “The Slang Vocabulary of the Legionnaires,” especially in its Forward and in Chapters 2–6. (2. Slang and loanwords used by legionnaires; 3. Figures of speech, idioms, and proverbs; 4. The most common German phrases; 5. The most common Arabic loanwords; 6. Bynames of ethnicities and nationalities in the slang used by legionnaires.)